Lana Bastašić est née à Zagreb en 1986. Elle a étudié l'anglais et obtenu un master en sciences de la culture, après quoi elle a publié deux recueils de nouvelles, un livre d'histoires pour enfants et une collection de poèmes. Son premier roman, Catch the Rabbit, est paru en 2018 à Belgrade avant d’être réimprimé à Sarajevo en 2019. Il a été sélectionné pour le NIN award en 2019 et traduit en catalan et en espagnol en 2020. Ses nouvelles ont été publiées dans des anthologies et magazines régionaux de l'ex-Yougoslavie. Elle a également reçu le prix de la meilleure nouvelle au concours littéraire Zija Dizdarević de Fojnica et au Ulaznica festival de Zrenjanin, , celui de la meilleure pièce de théâtre écrite par un dramaturge bosniaque (Kamerni teatar 55) à Sarajevo et, le Targa Unesco Prize for poetry à Trieste, et a été félicitée par le jury au festival « Carver: Where I’m Calling From » de Podgorica. En 2016, elle co-fonde Escola Bloom à Barcelone et y co-édite le magazine littéraire Carn de cap. Elle est aussi l'un des créateurs du projet « 3+3 sisters », qui vise à promouvoir les auteurs féminins des Balkans.

Agent / Rights Director

Publishing House

Translation Deals

- Bulgarian: Perseus

- Catalan: Periscopi

- Czech: Argo

- Dutch: Meulenhoff

- English: Picador UK, Restless Books (US & Canada)

- French: Actes Sud

- German: Fischer Verlag

- Greek: Gutenberg

- Hungarian: Metropolis

- Italian : Nutrimenti

- Macedonian: Artkonekt

- Serbian : Kontrast

- Slovenian : Sanje

- Spanish: Navona

- Russian : Eksmo Publishers

- Turquish: Ilksatir

Excerpt

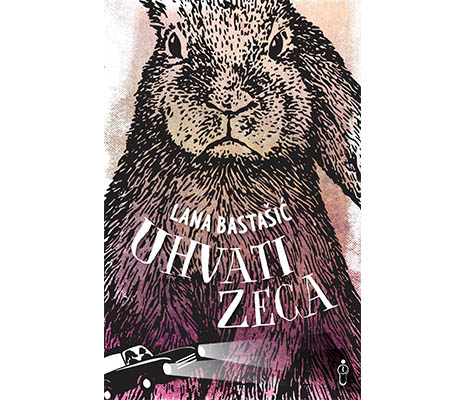

Uhvati Zeca - Lana Bastašić - Language: Bosnian

1

da počnemo ispočetka. Imaš nekoga i onda ga nemaš. I to je otprilike cijela priča. Samo što bi ti rekla da ne možeš imati drugu osobu. Ili da kažem ona ? Možda je tako bolje, to bi ti se svidjelo. Da budeš ona u nekoj knjizi. Dobro.

Ona bi rekla da ne možeš nekoga imati. Ali ne bi bila u pravu. Možeš posjedovati ljude za sramotno malo. Samo što ona voli sebe da posmatra kao nužno pravilo za funkcionisanje cijelog kosmosa. A istina je da možeš imati nekoga, samo ne nju. Ne možeš imati Lejlu. Osim ako je ne dokrajčiš, lijepo je uokviriš i okačiš na zid. Mada, da li smo to i dalje mi kad jednom stanemo? Jedno znam sigurno: zaustavljanje i Lejla nikada nisu išli zajedno. Zato i jeste tek razmazotina na sve i jednoj fotografiji. Nikada nije znala da se zaustavi.

Čak i sada, unutar ovog teksta, osjetim kako se koprca. Kada bi mogla, zavukla bi mi se između dvije rečenice kao moljac među dva rebra na venecijaneru, pa bi mi dokrajčila priču iznutra. Sebe bi preobukla u svjetlucave krpe kakve su joj se oduvijek sviđale, produžila si noge, povećala grudi, dodala koji val u kosu. A mene bi iskasapila, ostavila tek poneki pramen da visi preko četvrtaste glave, dala mi govornu manu, prošepala lijevu nogu, izmislila urođeni deformitet tako da mi olovka zauvijek ispada. Možda bi otišla i korak dalje, sposobna je ona za takvu podlost – možda me uopšte ne bi ni pomenula. Napravila bi od mene nedovršenu skicu. To bi ti učinila, zar ne? Pardon, ona. To bi ona učinila da je ovdje. Ali ja sam ta koja priča ovu priču. Mogu da joj uradim šta god želim. Ona mi ne može ništa. Ona je tri udarca u tastaturu. Mogla bih još večeras da bacim laptop u mukli Dunav, onda će i nje nestati, iscuriće joj krhki pikseli u ledenu vodu i isprazniti sve što je ikada bila u daleko Crno more. Prethodno će zaobići Bosnu kao grofica kakvog prosjaka na putu ka operi. Mogla bih da je završim ovom rečenicom tako da je više nema, da nestane, da se pretvori u blijedo lice na maturskoj fotografiji, da se zaboravi u urbanoj legendi iz srednjoškolskih dana, da se tek nazire u maloj hrpi zemlje koju smo ostavile tamo iza njene kuće pored one trešnje. Mogla bih da je ubijem tačkom.

Biram da nastavim zato što mi se može. Ovdje sam makar sigurna, daleko od njenog suptilnog nasilja. Nakon cijele decenije vraćam se svom jeziku, njenom jeziku i svim ostalim jezicima koje sam svojevoljno napustila, kao nasilnog muža, jednog popodneva u Dablinu. Poslije toliko godina, nisam sigurna koji bi tačno to jezik bio. A sve zbog čega? Zbog sasvim obične Lejle Begić, u izlizanim patikama na čičak i farmerkama sa, pobogu, cirkonima na dupetu. Šta se uopšte desilo između nas? Da li je to važno? Dobre priče ionako nikada nisu o onome što se dešava. Ostaju samo slike, poput crteža na trotoaru, godine padaju po njima kao kiša. Možda bi trebalo da napravim od nas slikovnicu. Nešto što niko sem nas dvije neće shvatiti. Ali i slikovnice treba nekako da počnu. Mada naš početak nije tek ćutljivi sluga hronologije. Naš je početak bio i prošao nekoliko puta, vukao me je za rukav kao gladno kuče. Hajde. Hajde da počnemo opet. Mi smo neprestano počinjale i završavale, uvukla bi se u membranu moje svakodnevice kao virus. Ulazi Lejla, izlazi Lejla. Mogu početi bilo gdje. Na primjer u Parku Sv. Stefana u Dablinu. Telefon vibrira u džepu mantila. Nepoznati broj. Onda stisnem ono prokleto dugme i kažem da? na jeziku koji nije moj.

„Halo, ti.”

Nakon dvanaest godina potpune tišine, ponovo čujem njen glas. Govori brzo, kao da smo se tek juče razišle, bez ikakve potrebe da se premoste rupe u znanju, prijateljstvu, hronologiji. Mogu da kažem samo jednu jedinu riječ: „Lejla.” Ona, po običaju, ne zatvara. Pominje restoran, posao u restoranu, nekog tipa čije ime prvi put čujem. Pominje Beč. Ja i dalje samo „Lejla”. Njeno je ime naizgled bilo bezazleno – sićušna stabljika usred mrtve zemlje. Iščupala sam ga iz svojih pluća misleći da je to ništa. Lej-la. Ali s tom je nedužnom grančicom izronilo iz kaljuge najduže i najdeblje korijenje, čitava šuma slova, riječi i rečenica. Čitav jezik sahranjen duboko u meni, jezik koji je strpljivo čekao tu malu riječ da protegne svoje okoštale ekstremitete i ustane kao da nikada nije ni spavao. Lejla.

„Odakle ti ovaj broj?” pitam je. Stojim nasred parka, zaustavila sam se tik ispred jednog hrasta i ne mičem se, kao da očekujem da se drvo pomakne u stranu i pusti me da prođem.

„Kakve to veze sad ima?” odgovara ona i nastavlja svoj monolog: „Slušaj, moraš da dođeš po mene... Je l’ me čuješ? Slaba je veza.”

„Da dođem po tebe? Ne razumijem. Šta...”

„Da, da dođeš po mene. Ja sam u Mostaru i dalje.”

I dalje. Za sve godine našeg prijateljstva nije nijednom bila pomenula Mostar, niti smo ikada tamo otputovale, a sada je odjednom predstavljao neospornu, opštepoznatu činjenicu.

„U Mostaru? Šta ćeš u Mostaru?” pitam je. I dalje gledam u drvo i brojim u glavi godine. Četrdeset i osam godišnjih doba bez njenog glasa. Znam da sam negdje krenula, ima ta moja putanja veze sa Majklom, i zavjesama, i apotekom... Ali Lejla je rekla rez i sve je stalo. Drveće, tramvaji, ljudi. Kao umorni glumci.

„Slušaj, to je duga priča, Mostar... Ti i dalje voziš, je l’ da?”

„Vozim, ali ne kontam šta... Je l’ ti znaš da sam ja u Dablinu?” Riječi mi ispadaju iz usta i lijepe se po mom mantilu kao gomila čičaka. Kad sam posljednji put govorila taj jezik?

„Da, vrlo si važna”, kaže Lejla, već spremna da obezvrijedi sve što sam mogla da doživim u njenom odsustvu. „Živiš na ostrvu”, kaže, „i vjerovatno čitaš onu dosadnu knjižurinu po cijele dane i ideš na branč sa svojim pametnim prijateljima, je l’ de? Super. Nego slušaj... Treba da dođeš po mene što prije. Moram do Beča, a oduzeli mi ovi majmuni ovdje vozačku i niko ne konta da moram...”

„Lejla”, pokušavam da je prekinem. Čak i nakon svih tih godina, savršeno mi je jasno šta se dešava. To je ona njena logika prema kojoj je gravitacija kriva ako te neko gurne niz stepenice, sve drveće je posađeno kako bi ona mogla da se popiša iza istoga, a svi putevi, koliko god krivudavi i daleki bili, imaju jednu zajedničku tačku, isti čvor – nju. Rim je šala.

„Slušaj me, nemam mnogo vremena. Stvarno nemam koga drugog da pitam, svi nešto seru da su zauzeti, istina nije baš ni da imam nešto mnogo prijatelja ovdje, a Dino ne može da vozi zbog koljena...”

„Ko je Dino?”

„...tako da kontam ako odletiš za Zagreb još ovaj vikend i sjedneš na autobus, mada bi Dubrovnik bio bolja opcija.”

„Lejla, ja sam u Dablinu. Ne mogu jednostavno da dođem po tebe u Mostar i vozim te do Beča. Jesi li ti normalna?”

Ona ćuti neko vrijeme, vazduh joj napušta nosnice i udara u telefon. Zvuči kao strpljiva majka koja se svim silama bori da ne lupi šamar djetetu. Nakon nekoliko trenutaka njenog teškog disanja i mog gledanja u tvrdoglavi hrast, kaže mi jednu riječ: „Moraš.”

Excerpt - Translation

Translated from Bosnian by the author

1

To start from the beginning. You have someone and then you don’t. And that’s the whole story. Except you would say you can’t have a person. Or should I say she? Perhaps that’s better, you’d like that. To be a she in a book. All right, then.

She would say you can’t have a person. But she would be wrong. You can own people for embarrassingly little. Only, she likes to think of herself as the general rule for the workings of the whole cosmos. And the truth is you can have someone, just not her. You can’t have Lejla. Unless you finish her off, put her in a nice frame and hang her on the wall. Although, is it really still us once we stop, once we freeze for the picture? One thing I know for sure: stopping and Lejla never went together well. That’s why she is a blur in every single photograph. She could never stop.

Even now, within this text, I can almost feel her fidget. If she could, she would sneak between two sentences like a moth between two slats on a Venetian blind, and would finish my story off from the inside. She would change into the sparkly rags she always liked, lengthen her legs, enhance her breasts, add some waves to her hair. Me she would disfigure, leaving a single lock of hair on my square head; she would give me a speech impediment, make my left leg limp, think up an inherent deformity so I keep dropping the pencil. Perhaps she would take it one step further, she is capable of such villainy – she wouldn’t even mention me at all. Turn me into an unfinished sketch. You would do that, wouldn’t you? Sorry – she. Lana Bastašić

She would do that if she were here. But I am the one telling the story. I can do whatever I want with her. She can’t do anything. She is three hits on the keyboard. I could throw the laptop into the mute Viennese Danube tonight and she would be gone, her fragile pixels would bleed into the cold water and empty everything she ever was out into the Black Sea, dodging Bosnia like a countess dodges a beggar on her way to the opera. I could end her with this sentence so that she no longer is, she would disappear, become a pale face in a prom photo, forgotten in an urban legend from high school, mentioned in some drunk moron’s footnote where he boasts of all those he had before he settled down; she would be barely detectable in the little heap of earth we left there behind her house next to the cherry tree. I could kill her with a full stop.

I choose to continue because I can. At least here I feel safe from her subtle violence. After a whole decade, I go back to my language – her language, and all the other languages I voluntarily abandoned, like one would a violent husband – one afternoon in Dublin. After all these years, I’m not sure which language that is. And all that because of what? Because of the totally ordinary Lejla Begić, in her old sneakers with straps and jeans with, for god’s sakes, diamanté on the butt. What happened between us? Does it matter? Good stories are never about what happens anyway. Pictures are all that’s left, like pavement paintings, years fall over them like rain. But our beginning was never a simple, silent observer of chronology. Our beginning came and went several times, pulling on my sleeve like a hungry puppy. Let’s go. Let’s start again. We would constantly start and end, she would sneak into the fabric of the everyday like a virus. Enters Lejla, exits Lejla. I can start anywhere, really. Dublin, St. Stephen’s Green, for instance. The cellphone vibrating in my coat pocket. Unknown number. Then I press the damn button and say yes in a language not my own.

‘Hello, you.’

After twelve years of complete silence, I hear her voice again. She speaks quickly, as if we parted yesterday, without the need to bridge gaps in knowledge, friendship, and chronology. I can only utter one word, Lejla. As always, she won’t shut up. She mentions a restaurant, a job in a restaurant, some guy whose name I’ve never heard before. She mentions Vienna. And I, still, just Lejla. Her name was seemingly harmless – a little shoot amidst dead earth. I plucked it out of my lungs thinking it meant nothing. Lejla. But along with the innocent stem, the longest and thickest roots came spilling out from the mud, an entire forest of letters, words and sentences. A whole language buried deep inside me, a language that had waited patiently for that little word to stretch its numb limbs and rise as if it had never slept at all. Lejla.

‘Where did you get this number?’ I ask. I’m standing in the middle of the park, stopped right in front of an oak, paralyzed, as if waiting for the tree to step aside and let me past.

‘What does it matter?’ she answers and goes on with her monologue, ‘Listen, you gotta come pick me up... Can you hear me? The connection’s bad.’

‘Pick you up? I don’t understand. What…’

‘Yeah, pick me up. I’m still in Mostar.’

Still. During all those years of our friendship she had never once mentioned Mostar. We had never been there, either, and now it somehow represented an indisputable, common-knowledge fact.

‘In Mostar? What are you doing in Mostar?’

I’m still looking at the tree, counting the years in my head. Forty-eight seasons without her voice. I know I’m going somewhere, my route has something to do with Michael, and the curtains, and the pharmacy, but all that has come to a standstill now. Lejla showed up, said cut, and everything froze. Trees, trams, people. Like tired actors.

‘Listen, Mostar is a long story… You still drive, right?’ ‘I do, but I don’t get what… Do you know I’m in Dublin?’

I keep looking around me afraid that someone would hear me. Words fall out of my mouth and stick to my coat like burrs. When was the last time I spoke that language?

‘Yeah, you’re very important,’ Lejla says, ready to devalue the entirety of what I might have lived in her absence. ‘Living on an is-land, probably reading that boring big-ass book all day long, having brunch with your brainy friends, right? Awesome. Anyway, listen… You gotta come get me as soon as you can. I gotta go to Vienna and these morons took my license and nobody gets that I have to...’

‘Lejla,’ I try to interrupt her. Even after all these years it is perfectly clear to me what’s going on. It’s that particular logic of hers that says gravity is to blame if someone pushes you down a flight of stairs, that all trees were planted so that she could take a piss be-hind them, and that all roads, no matter how meandering and long, have one connecting dot, the same knot – her. Rome is a joke.

‘Listen, I don’t have a lot of time. I really have no one else to ask, everyone’s bullshitting me with how busy they are, not that I have a lot of friends here to be honest, and Dino can’t drive ’cause of his knee…’

‘Who’s Dino?’

‘… so I was thinking you could fly to Zagreb this weekend and get on a bus, though maybe Dubrovnik would be better.’

‘Lejla, I’m in Dublin. I can’t just pick you up in Mostar and drive you to Vienna. Are you insane?’

She’s quiet for a while; the air leaves her nostrils and hits the receiver. She sounds like a patient mother doing her best not to slap a little kid. After some moments of her heavy breathing and my staring at the stubborn oak, she says, ‘You have to.’