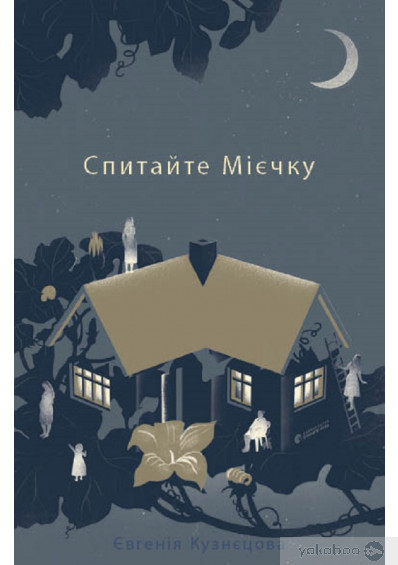

Eugenia Kuznetsova est une autrice, traductrice et chercheuse ukrainienne. Elle a passé l’intégralité de son enfance dans son village natal de Khomutyntsi, en Ukraine centrale. Après des études à l’Université nationale de Kiev, elle obtient un doctorat en analyse littéraire en Espagne. Eugenia travaille aujourd’hui dans la recherche sur les médias, se focalisant sur la couverture des conflits et la lutte contre la désinformation. Elle traduit des ouvrages de fiction et de non-fiction, et a publié deux livres jusqu’à présent. Son premier ouvrage, Готуємо в Журбі (Cuisiner dans la douleur), paraît en 2020. Son deuxième ouvrage, Спитайте Мієчку (Demandez à Mietchka), est retenu en 2021 pour le prix « BBC News Ukraine Book of the Year ». Elle travaille aujourd’hui sur une monographie qui traite des politiques linguistiques et identitaires de l’Union soviétique, ainsi que sur un autre roman. Les deux ouvrages doivent être publiés en 2022.

L’histoire de Demandez à Mietchka met en scène quatre générations de femmes au cours d’un été. Deux sœurs, Mia et Lilia, se rendent dans leur « refuge », une vieille maison de leur grand-mère où elles ont passé leur enfance, pour tenter de mettre en attente les décisions qui vont changer leur vie : décider d’immigrer ou de rester, choisir entre un homme fiable et un amour sauvage. Leur grand-mère, Thea, approche de la fin de sa vie et sa fille, la mère des deux sœurs, craint de prendre la place de la femme la plus âgée de la famille.

La vieille maison, envahie par les mauvaises herbes, les arbustes et les arbres tentaculaires, semble figée dans le temps, perdue dans l’oubli. Pourtant, les sœurs lui redonnent vie : de nouvelles personnes arrivent, de nouveaux chats se promènent, des citrouilles poussent et le porche est rénové. La maison change, tout comme la vie des femmes qui l’habitent, alors que l’été touche à sa fin.

Dans son roman, Eugenia Kuznetsova raconte une histoire profondément intime sur les relations entre sœurs, mères et filles. Des dialogues vivants, où les choses les plus sensibles restent inexprimées, mais sont en quelque sorte ressenties, définissent l‘atmosphère de l’histoire et soulignent les liens uniques qui existent entre les générations de femmes d’une même famille.

Agent / Rights Director

Publishing House

Excerpt

Приїхали

— Кожна жива істота має право на притулок, — казала Мієчка за кермом.

— На зарослий кущами шелтер, — відказувала її сестра Лілічка.

Поки вони мовчали, були абсолютно різні: в однієї — хвилясте волосся, в іншої — пряме, як у китаянки. Мієчкині щоки завжди мали ледь персиковий відтінок, а Лілічка була бліда, наче все життя провела у бетонній коробці, куди ніколи не потрапляє сонце. Але коли сестри

починали говорити, якимось чином ставали схожі. З кожним словом їхні очі, губи, вуха, рухи все більше зливались, аж поки співрозмовник не заплющував очей, не тряс головою і не казав: «Хто з вас говорить?». Вони тоді переглядались, якусь мить мовчали і знову ставали різними — як день і ніч.

У зарослий кущами притулок для лузерів вони при- їздили завжди, коли без цього вже було не можна. Для цього не треба було трагедій — просто іноді видавалося, наче все в тумані і дороги далі не видно. Тоді наставав час для шелтеру. Притулок являв собою будинок із величезними непропорційними вікнами, витертою підлогою і згнилою терасою, весь зарослий кущами, малиною, ожиною, хмелем, високими тополями, березами, здичавілими сливами, яблуками й грушами. У тих кущах вони й виросли, програли битву заростям і хащам, звідти й поїхали. Він стояв, як докір минулому про те, що ніколи там не буде так, як раніше. Ніколи вже не спати- муть усі по троє, ніколи чоловіки не казатимуть «я ляжу надворі» і не лягатимуть на дерев’яних настилах попід деревами, струшуючи з себе усю ніч випадкових кажанів, котів і комах із безкінечною кількістю ніг. Усі ці люди давно розбіглися, вмерли, загубились, і про них нагадував тільки різноманітний мотлох, названий їхніми іменами. «Подай-но мені гончаровську вазу», — казала бабуся. Ніхто в домі того Гончарова й не знав, і не пам’ятав, але ваза була його імені.

На місці будинку колись була хата, а потім невмолимий час її перемолов, лишивши провалену стріху, хлів по груди в землі і зворушливу драбину коло віконця для птиці. Більше жодній птиці не судилося сидіти на тій драбині, окрім випадкових жовтих вивільг. Колись на це місце бабусю привіз чоловік, знявши її з п’ятого поверху в центрі міста, забравши її від батьківських фікусів, бібліотеки і розшитої золотом скатерки.

— Це той рай, про який ти мені казав? — спитала тоді юна ще Теодора, дивлячись на старий хлів і на залишки розваленої хати, яку наче розбило судомами.

— Це він, — чула вона у відповідь і розуміла, що любила цей голос так, що ніякі фікуси їй не були потрібні.

Минули десятки років, поки сліди старої хати зникли, а на її місці виріс будинок і зістарився разом із Теодорою. Тут виростали діти, звідси вони поїхали, виросли онуки, тут бавилися правнуки. Тепер Теодора, підбираючись до своїх ста літ, сиділа на зігнилій терасі, пробрав- шись через стежку, що вся заросла ожиною, і чекала на своїх біженок, які прямували до неї в кущі.

Спершу у притулок тікали через екзистенційні переживання про померлих папуг і черепах. Потім через кар’єрні кризи, любові, дітей. Лілічка у притулку колисала синів тоді, коли у звичайних умовах вони її доводили до божевілля. В шелтері для лузерів діти раптом ставали спокійні і просто повзали заростями ожини, дряпаючи свої ніжні, м’які животи. Мієчка тут вирішувала, куди рухатись далі. У шелтері ідеї не приходили до голови, зате приходило усвідомлення, що колись таки прийдуть. Тут навіть можна було змиритись із відсутністю ідей, рубаючи ті непролазні хащі.

— Страшно уявити, що роблять люди, в яких немає будинку в дикій малині, — казала Лілічка.

Вона привезла ледь рожеві туфлі з відкритими пальцями, щоб Мієчка їх одразу взула — туфлі лежали на горищі років сорок; бабуся купила їх колись у Вільнюсі, але розмір був не її, тому так ніколи їх і не взула, і зараз не знала, що час їхній настав. Лілічка їх знайшла, поки прибирала на горищі в нервовому припадку. Хто ж знав, що сорок років тому бабуся купила туфлі точно такого розміру, якого будуть чотири ноги її двох майбутніх онучок.

— Ти зараз вийдеш з машини, і бабуся упаде, — казала Лілічка, роздивляючись сестрине плаття. Вона була офіційно красивою. Носила темні окуляри, майку без нічого під нею і джинси з дірками.

— А тобі скаже, — відповідала Мієчка, — чого ти не можеш вдягатись, як сестра?

— Вона ж не знає, що весь інший час ти носиш оте своє плаття кольору і фасону мішка під картоплю, — казала Лілічка, блискаючи окулярами у заднє дзеркало.

— Зате коротке.

— Тим більше коротке.

Потім вони стали на заправці. Світило перше спекотне червневе сонце, десь там під яблунями дозрівали суниці їхнього дитинства, а Мієчка витягла з багажника свою валізу і звідти дістала небесно-голубий сарафан у білі квіточки.

— О! — сказала Лілічка.

— Вдягай! — усміхнулась Мієчка.

Лілічка відчинила задні двері машини, швидко скинула свою майку, і сарафан легкою хвилею скотився з плечей за коліна.

— Бабуся точно упаде, — сказала Лілічка.

Вперше за вісім років ситуація була така, що реабілітація була потрібна на все літо.

Вони розіслали листи чоловікам, бойфрендам, колишнім чоловікам і всім причетним. І склали графік для Лілічкиних дітей.

— Пам’ятаєш, — сказала Мієчка, однією рукою шукаючи радіостанцію, а другою поправляючи собі рукав плаття, — раніше літо було безкінечне, правда?

Лілічка просто кивнула, однією рукою тримаючи кермо замість Мієчки. Іншою рукою вона терла яблуко об власне коліно, на якому легкою синьою хвилею лежав щойно подарований сарафан. Вони так робили завжди — коли одна бралася поправляти бретельки, то інша автоматично брала кермо в свої руки.

Приїхали вже під вечір.

Excerpt - Translation

Translated from Ukrainian by Reilly Costigan-Humes and Isaac Wheeler

We’re Here

“Every living being has the right to shelter,” said Miechka, who was driving.

“To a shelter overrun by bushes,” replied her sister Lilichka.

Before they started talking, they were absolutely different. One’s hair was wavy, the other’s hair so straight it almost made her look Chinese. Miechka’s cheeks had a peachy shade to them, while Lilichka was pale, like she’d spent her whole life in a concrete bunker that never got any sunlight. Yet, as soon as the two sisters began speaking, a certain similarity emerged. With every word, their eyes, lips, ears, and movements blended together more and more up until whoever was conversing with them could close their eyes, shake their head, and say, “Who’s even talking?” Then they’d exchange a glance, fall silent for a moment, and then, once again, they’d become as different as night and day.

They came to the overgrown shelter for losers whenever they had no other choice. That didn’t require a tragedy of anything – at times, it just seemed like everything was foggy and the road ahead was obscured. That’s when it came time for the shelter. It was a structure with large, disproportionate windows, a faded floor, and a rotten deck overrun by bushes, raspberries, blackberries, barley, tall poplars, birches, wild plums, apples, and pears. They grew up amid those bushes, lost the battle to the thickets and overgrowth, and then left.

The shelter stood, reproaching the past for the fact that things there would never be like they used to be. Never again would all of us sleep in groups of three, never again would the men say “I’m going to sleep outside,” lie down on planks under the trees, and spend all night shaking off stray bats, cats, and insects with innumerable legs. All of those people scattered, died, or disappeared long ago, and the assorted junk bearing their names is the sole reminder of them. “Hand me Honcharov’s vase,” Grandma said. Nobody in the house had any idea who Honcharov was, but the vase was named after him.

Before the shelter, there used to be a house here. Then implacable time mashed it up, leaving behind the collapsed remains of a thatched roof, a barn full of chest-high piles of dirt, and a heart-warming ladder by a window for birds to perch on, yet no more birds, except for an occasional yellow oriole, were destined to sit there. Back in the day, Grandma’s husband brought her to this place, once he’d plucked her out of that fifth-floor apartment downtown and taken her away from her parents’ fig trees, library, and gold-embroidered tablecloth.

“Is this the paradise you were telling me about?” a young Theodora asked as she looked at the old barn and the remnants of a dilapidated house that had been obliterated by convulsions.

“This is it,” came the response, and she realized that she loved this voice so much that she didn’t need any fig trees whatsoever. Decades passed before every trace of the old house vanished and a new one matured and grew old with Theodora. Her children grew up here and then left; her grandchildren grew up here; her great-grandchildren played here. Now, Theodora, sneaking up on a hundred, sat on the rotten deck after she had fought her way down a path overrun by blueberries and waited for her refugee granddaughters who were heading toward her through the bushes. At first, they fled to the shelter due to existential anxieties over dead parrots and turtles. Then over professional crises, relationships, children. Here, Lilichka lulled her sons to sleep when, under regular circumstances, they drove her to the brink of insanity. At the shelter for losers, her children calmed down suddenly and simply crawled through thick patches of blueberries, scratching their tender bellies. Miechka would decide where to head next. At the shelter, ideas wouldn’t come to her, yet the realization that they eventually would did come. Here, you could come to terms with your lack of ideas as you sliced through impassable thickets.

“I shudder to think what people who don’t have a house overgrown with wild raspberries do,” Lilichka said once. She brought a pair of barely pink open-toed heels for Miechka to put on right away. Those heels had been up in the attic for about forty years; their grandma bought them way back when in Vilnius, but they didn’t quite fit her, so she never wore them, and she wasn’t aware that their time had come. Lilichka found them when she was cleaning the attic in a nervous fit. Who could have guessed that, forty years ago, her grandma bought heels that were the exact size of her two future granddaughters’ four feet?

“Granny’ll fall over when you step out of the car,” Lilichka said, eyeing her sister’s dress. Lilichka was certifiably beautiful. She was wearing dark glasses, a T-shirt with nothing underneath, and jeans with holes in them.

“And she’ll ask you why you can’t dress like your sister.” Miechka replied.

“She has no clue you wear that sack-of-potatoes dress most of the time,” Lilichka said, her glasses flashing in the rearview mirror.

“At least it’s short.”

“Yeah, and it’s short to boot!”

After that, they stopped at a gas station. The first sweltering sun of that June shone bright; the strawberries of their childhood were ripening under the apple trees. Miechka took her suitcase out of the truck and produced a sky blue sarafan with white flowers on it.

“Oh!” Lilichka said.

“Put it on!” Miechka said, smiling. Lilichka opened one of the back doors of the car, swiftly slipped out of her T-shirt, and the sarafan slid softly as a wave from her shoulders down over her knees.

“Granny’ll fall over, that’s for sure,” Lilichka said.

For the first time in eight years, things were such that they would need the whole summer to rehabilitate fully. They emailed all their husbands, boyfriends, ex-husbands, and all other interested parties and set a schedule for Lilichka’s kids.

“Remember how,” Miechka said, searching for a radio station with one hand and adjusting her dress sleeve with the other, “summer used to go on forever. Didn’t it?”

Lilichka simply nodded, holding the wheel with one hand for Miechka. With her other hand, she rubbed an apple on her knee, on the airy, blue wave of the sarafan that she’d just been gifted. That’s what they always did – whenever one of them had to adjust their straps, the other would take the wheel automatically.

They arrived in the early evening.