Ag Apolloni (Kosova, 1982) is an Albanian author. He studied Dramaturgy at the Faculty of Arts, and Literature at the Faculty of Philology, both at the University of Prishtina, where since 2008 he works as a Professor of Literature. In 2012, he earned his PhD in Literature. In 2013, he founded the cultural studies journal Symbol. He conducted interviews with Jonathan Culler, Linda Hutcheon, Mieke Bal, Stanley Fish, Peter Singer etc. His writings and works have been translated in several languages as English, German, Dutch, Czech.

© Picture Burim Myftiu

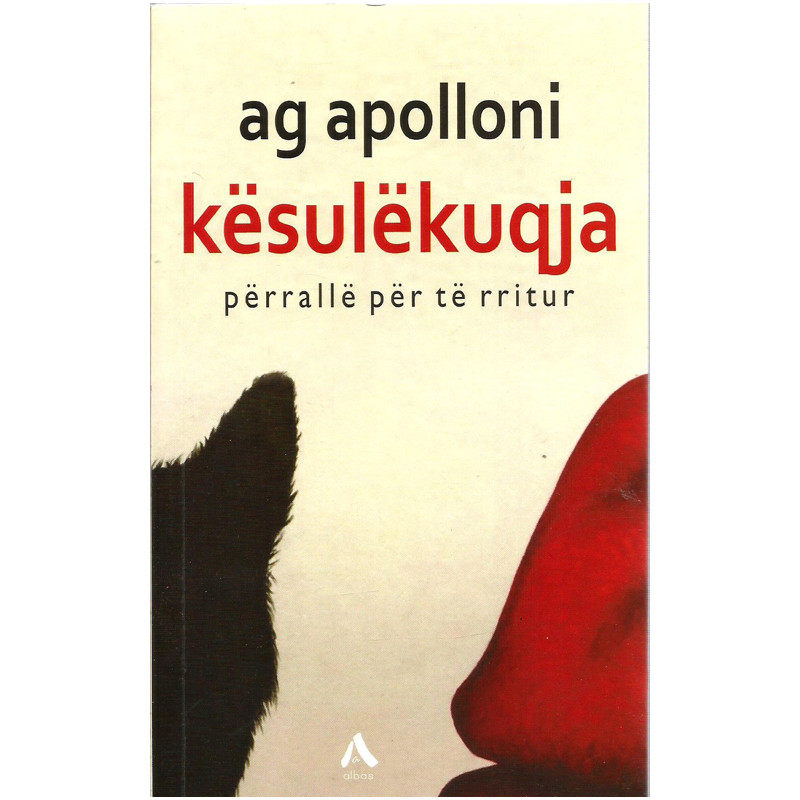

The latest novel of Ag Apolloni is a love story between a 40-year-old dramatist and a 20-year-old actress. The event happens in Prishtina in 2022. Lorita (the actress) was chosen to play Judita’s role in a show prepared by the National Theatre, while Max (the dramatist, the writer) is in a psychological crisis, not being able to write the novel about rapes during the war. He also has a health problem with his lungs as a result of Covid-19. Therefore, to get fresh air, he goes out in the park, where he meets the actress, who has gone out for a run. They meet in the park, surrounded by trees, Max in black as a sick wolf, Lorita with a red cap as a grown-up Red Riding Hood. And from that moment, love arises between them, which has its ups and downs throughout the novel.

Excerpt

Ag Apolloni

Kësulëkuqja, përrallë për të rritur

Bard Books, 2022

GJYSHJA E MBAROI përrallën dhe bëri sikur po më hante. Pastaj unë i thashë: Edhe? Gjyshja tha: Çka edhe? I thashë: Pasi i hëngri, çka ndodhi? Tha: Kurrgjë. I hëngri. U kry. Përralla në shkallë, dukati në ballë. Thashë: Jo, nuk u kry. Tha: U kry, merr vesh! Unë jo, ajo po, unë jo, ajo po. Dikur më bërtiti: Ik, se më lodhe, fëmijë i mërzitshëm! Atëherë, s’di se qysh më erdhi, - po fëmijë kam qenë, - e t’ia kam futë shuplakë gjyshes: bam! Veç kur ia kam pa syzet dhe protezën e dhëmbëve te pragu, para këmbëve të babit. Aty e kuptova sa është sahati, dhe mora turr kah dritarja. Meqë salloni ishte në katin e parë dhe nga vapa e mbanim dritaren hapë, arrita të shpëtoj nga kthetrat e tij. Unë e kisha kalu’ oborrin, kur babi u shfaq në dritare. Nuk guxova me u kthy, derisa u lëshu’ mami prej punës.

- Hahaha. Vërtet i ke ra shuplakë gjyshes?,- pyeti Maksi.

- Po. Bile ajo shpesh thoshte as burri jem, rahmetliu, s’e ka pasë dorën ma të randë,- e imitoi gjyshen, dhe pastaj piu lëng portokalli

nga shishja e saj me cucëll. Mjaft e vogël dukej, por ta shihje duke pirë me atë shishe, dukej edhe më e vogël, një trohë.

Ai qeshte sa me tregimin, aq edhe me imiti- min e saj.

- Ti je fëmija i vetëm që e ka rrahë gjyshen, prejse ekzistojnë gjyshet dhe përrallat.

- Po ajo e meritonte. Për shembull, unë e kisha edhe tjetrën gjyshe, por ajo ma tregonte përrallën ndryshe. Mbasi i hante Ujku të dyja, vinte gjahtari, e gjente Ujkun, ia çante barkun, i nxirrte gjyshen dhe Kësulëkuqen, mandej ia mbushnin Ujkut barkun me gurë, ia qepnin dhe, ai, kur zgjohej, shkonte drejt pusit për me shue etjen dhe binte aty brenda. Fundi i përrallës. Bile, ajo gjyshja nga mami, kur s’përtonte, tregonte edhe detaje të tjera: se si vazhdonin ata tre të pinin çaj nën hijen e arrës dhe t’i tregonin njëri-tjetrit historinë me Ujkun. Kësulëkuqja thoshte: po unë s’e kam ditë, se kurrë s’i kisha tregu’ Ujkut; gjyshja e saj tregonte: sikur jam kanë tu nejtë, veç kur ka hy diçka me turr, edhe t’m’u ka hedhë përmbi, edhe mâ sen’ s’kam pa; gjahtari, duke shkundë kapelën, fliste: e dëgjova një gërhatje, ish aq e fuqishme, sa kulmin e çonte përpjetë, e disha që insani s’gërhet ashtu. Bile-bile, gjyshja nga mami, njëherë më pati tregu’ sesi Kësulëkuqja mbas disa vjetësh kishte mbetë jetime, pa nanë, kurse baba i ishte martu’ dhe kishte bâ fëmijë me gruen e re, e cila nuk e donte Kësulëkuqen, të cilën e detyronte të punonte si shërbëtore për të dhe vajzat e saj, derisa një ditë, pa dijen e njerkës, kjo mori pjesë në një ballo ku e humbi këpucën, por e gjeti fatin... E kështu, lamsh m’i

bënte përrallat: Kësulëkuqja bëhej Hirushe, Hirushja Borëbardhë e ku ta di unë. Ama, ishte fantastike, ta ndizte imagjinatën, të kënaqte. Unë doja që historia të vazhdonte, dhe ajo e vazhdonte derisa më merrte gjumi. Kurse kjo gjyshja nga babi: e hangri Ujku dhe u kry! Jo, bac, s’u kry, i thashë, dy lidhje me cartoon logic s’i ki. Nuk e dinte se përrallat nuk përfundojnë me vdekje. Duhet një happy end patjetër.

- E shkreta, nuk e paska lexu’ as Propp-in.

- Po, sigurisht. Ajo është analfabete, - tha vajza duke e prekur strehën e kapelës së saj të kuqe sportive.

- Kot i ke ra shuplakë gjyshes. Ajo ta ka tregu’ një version të hershëm, të bazuem në një version edhe ma të hershëm, të para njëmijë vjetësh.

- Qysh përfundon ai version?

- Ujku shkon në shtrat me Kësulëkuqen dhe fund.

- Hm. Shkon në shtrat? Domethënë...?

- Ëhë.

- Po kjo s’është për fëmijë.

- Po, Kësulëkuqja para se të bëhej përrallë për fëmijë, ishte histori për të rritur. E tregonin fshatarët francezë. Argëtoheshin me një histori përdhunimi, ose thjesht me një histori erotike, meqë shumë interpretues thonë se Kësulëkuqja e lejon veten qëllimisht të joshet nga Ujku, dhe kështu, duke bâ dashni me të, kalon nga faza e adoleshencës, në fazën e pjekurisë.

- Uh, kuçka që paska qenë!, - tha ajo duke qeshur, dhe duke nxitur të qeshurën e tij.

- Bile, krejt në fillim, antagonisti nuk ishte ujk, po një njeri-ujk, lykantropos, ose werewolf.

Në Mesjetë, kur bëheshin ato gjyqet e tmerr- shme, persekutoheshin, torturoheshin e vrite- shin në mënyrat më të tmerrshme ata që supo- zohej se ishin lykantropë.

- Çka bënin lykantropët?

Ata ishin në parkun e Tokbashçes, ku ai zakonisht në mëngjes dilte për të ecur dhe për të kërkuar ajër të pastër për mushkërinë e tij të sëmurë. Aty kishte gjelbërim, lule, ngjyra dhe, po, rreze, natyrisht.

- Uluronin, - tha duke ngrehur kokën lart. I pëlqente kjo trajtë, në vend të asaj të butës: ulërinin.

- Vampirë?

- Pastaj i hanin Kësulëkuqet, - shtoi ai duke ia ngulur sytë kapelës së saj të kuqe.

- Domethanë, vërtet i hanin çikat e reja?

Kështu thoshte shoqëria e asaj kohe. Shoqëri besëtyte. Ndoshta të tjerë njerëz përdhunonin dhe ua hidhnin fajin atyre. Apo ndoshta edhe ata përdhunonin, por sigurisht nuk i hanin. Krejt çka mund të bënin ata ishte të flinin me çikat, dhe mandej të jepnin material për histori tavernash, ku njerëzit deheshin dhe fantazonin duke u gajasë e gogësitë.

- Pra, Ujku ishte njeri?

- Ashtu duket.

- Apo njeriu ishte ujk?

- Edhe kështu mund të thuhet.

- Eh, përralla!

- Asnjë përrallë nuk është vetëm përrallë.

- Mendoj se nuk ka kurrgjë të keqe të jesh ujk.

- Sigurisht.

- Jeton i vetmuem...

- Edhe kur del me shokë, del me ujq e jo me qen...

- Ha mish të freskët...

- Del natën dhe i uluron hanës...

- Ah, po! Ky është imazhi më i bukur...

- ...dhe më domethënës.

Ajo e shikoi në sy, pastaj uli kokën.

- Pse i ke sytë e kuq?

Me të pa ty më mirë, - ia ktheu ai, pa i penguar fare që ajo po i drejtohej në një mënyrë joformale, edhe pse ky takim rastësor ishte i pari mes tyre.

- Hahaha. Jo, jo, vërtet po të pyes?

- Sepse nuk pata fat t’i kem blu.

- Eh, blu mund t’i ketë vetëm Kësulëkuqja, - tha ajo dhe puliti qepallat, mandej preku kape- lën me dorën e saj të djathtë, thonjtë e gishtave të së cilës ishin lyer me blu.

Maksit i bëri përshtypje gjithçka e saj – mollëzat sllave, hunda e vogël, buzët mishtore, gjinjtë që i dukeshin të mëdhenj nën duks, shkurt e shqip, i pëlqente gjithçka e saj – por sytë, sytë blu, ata sy ashtu, e habitën, e goditën, e tronditën më së shumti. Kësi sysh do të ketë pasur edhe Elsa e Aragonit. Sytë e tu e sfidojnë qiellin kur hapet moti, kujtoi ai.

- A mendon se regjisori ka bërë mirë që më ka zgjedhë mua për rolin e Juditës?, - pyeti ajo.

- Po ta kisha ditë që ndonjëherë dikush si ti do ta luajë atë rol, do ta kisha shkru’ shumë më mirë.

- Ka shumë tekst, më këputi. Sikur ta kishe shkurtu’ pak, do ta kisha më lehtë me e mësu’.

- Mund ta shkurtojë regjisori.

- Oh, e njeh Metin ti? Thotë s’mund ta shku- rtoj, se s’durohet autori mandej. Njëmend, thotë se je shumë i padurueshëm dhe... mendjemadh.

- Mendjemadh? Epo, nga mendja e vogël s’ka dalë asnjëherë ndonjë vepër e madhe.

Një çift i vjetër kaloi para tyre, plaka kishte një qëndrim konkav, kurse plaku konveks; ajo i merrte erë tokës, ai qiellit.

- E, ti çka mendon për Juditën?, - e pyeti Maksi Kësulëkuqen.

- Kam lexu’ drama edhe më të dobëta, - ia ktheu ajo, duke e mbledhur grushtin dhe duke e prekur strehën e kapelës me gishtin e mesëm. Ai e kuptoi se ku shenjonte ai gisht, dhe, sado që u përpoq të rrinte serioz, njëri cep i buzës i kishte ikur.

- A je i martuem?, - ia ndërroi ajo rrjedhën bisedës papritur.

Ai e shikoi sikur t’i thoshte “epo, tash e teprove. Edhe liria duhet të ketë njëfarë kufiri”. Por, nuk foli, vetëm e pa dhe heshti.

- Nuk të kujtohet?, - ironizoi ajo duke u lëpirë.

Ai buzëqeshi, dhe kjo buzëqeshje ishte dorëzim para ngacmimeve të saj seksuale për të cilat, siç dukej, ai nuk e kishte ndërmend ta padiste atë.

- Jo, nuk jam, - ia ktheu më në fund.

- Domethënë, jeton vetëm, apo jo?, - vazhdoi ta ngacmonte ajo.

- Jo.

- Me kë, atëherë?

- Me fantazmat e mia, - tha ai, dhe shikoi njerëzit me pantolla të shkurta që po vraponin në shtegun e shtruar me gomë.

- Ke cigare?

- Jo, Kësulëkuqe. Dhe mendoj se s’duhet ta pish. Nuk dilet në park me pi cigare.

- Faleminderit për kujdesin, xhaxhi ujk, - i tha duke e vënë theksin te fjalët e fundit, sa për t’ia përkujtuar moshën, aq edhe për t’ia nxitur dëshirën.

Ai e shikoi atë, por ajo kishte ulur kokën dhe po kërkonte në xhepa, ku e gjeti një cigare dhe një shkrepëse, dhe e ndezi. Ai shihte strehën e kapelës së kuqe dhe buzët e kuqe të fryra, mes të cilave u fut lehtë dhe ngadalë cigarja e bardhë. Çka të kisha hangër, tha Ujku brenda tij, ndërsa me zë shtoi:

- Më duhet të shkoj.

Ajo e pa e befasuar. S’e kuptonte, ose shtirej sikur s’e kuptonte çfarë ndodhi.

- Më vjen mirë që u njohëm, - tha ai dhe u çua.

- Ej, xhaxhi, para se me shku, a po ma sugjeron ndonjë këngë?, - i tha ajo, duke i treguar kufjet.

Ai nuk u mendua gjatë dhe i tha:

- Li’l Red Riding Hood nga Sam The Sham & The Pharaohs, - dhe u largua duke marrë frymë me vështirësi.

Ajo e shtypi këngën në telefon, dhe para se t’i vinte kufjet në vesh e të shkonte te stoli ku po e prisnin shoqet me veshje sportive, i tha:

- A del përditë në park?

- Jo..., po..., shpesh.

- Paske nevojë, se t’u paska fry barku si me i pasë hangër gjyshen dhe Kësulëkuqen.

Ai vetëm buzëqeshi, pa e kthyer kokën, dhe pa e kuptuar që ajo po e përshëndeste me

gishtin e mesëm, ndërkohë që po vallëzonte për ta ndjekur ritmin e këngës:

Owo!

Who's that I see walkin' in these woods? Why, it's Li’l Red Riding Hood.

Hey there Li’l Red Riding Hood, You sure are looking good.

You're everything a big bad wolf could want.

Excerpt - Translation

Little Red Riding Hood: A Fairy Tale for Adults

Ag Apolloni

Translated into English by Suzana Vuljevic

“Granny finished the story and pretended to bite me. I begged her to keep on going. And…I said, and she’d go, and what?

After the wolf ate them, what happened?”

‘Nothing. He ate them. The end,’ she said. ‘And they all lived happily ever after.’

‘No, that’s not all.’

‘It is. Get it through your head!’ When I would say no, she’d say yes, and it’d go on and on.

At some point, she shouted: ‘Scram, I’ve had it with you, you little brat!’ Then I’m not sure what came over me,—I was a kid after all—but I slapped my grandmother. Whack! It was only when I saw her glasses and dentures in the doorway at my father’s feet, that I understood what was coming to me, and I rushed to the window. Considering that the living room was on the first floor and we left the window open because it was so hot, I managed to escape my father’s clutches. I’d already made it past the yard when he appeared in the window. I didn’t dare go back home until mom was back from work.”

“So you really slapped your grandma?” Max asked, laughing.

“Yeah, believe it or not, she used to say not even my husband, God rest his soul, had such a heavy hand,” she said, imitating her grandmother.

“And then she’d take a swig of orange juice from her baby bottle. She was already a little old lady, but seeing her drink from that bottle made her look even tinier.”

He found her play-by-play of events even funnier than the story itself.

“You’re the only kid in the entire history of grandmothers and fairytales that ever slapped her own grandmother.”

“Oh, but she deserved it. I mean, I had another grandma who’d tell the story differently. After the wolf ate the grandmother and Little Red Riding Hood, a hunter comes, finds the wolf, cuts its stomach open, and pulls them both out. Then they fill the wolf’s belly with stones, stitch it up so that when he wakes up, he goes to the well to quench his thirst and ends up falling in. That’s the end. And get this, when my grandma on my mom’s side wasn’t too tired, she’d throw in other details, like how the three of them would get together to have tea under a walnut tree and trade stories about the wolf. Little Red Riding Hood would say, but I didn’t know, because if I had, I never would’ve told the wolf. The grandmother would say, while I was sitting there something came running in out of nowhere, and jumped on top of me, and I couldn’t see a thing. The hunter, shaking his hat out, said, I heard snoring so loud that it sent the roof flying, and I knew that no human snores like that. In fact, my grandma on my mom’s side once told me that years later Little Red Riding Hood became an orphan. Her dad married another woman and he had a kid with the new wife. The new wife didn’t like Little Red Riding Hood and made her work as a servant to her and her daughters, until one day, without her stepmother knowing, the girl went to a ball and lost her slipper, but met her destiny… And that’s how she’d mix up all my stories. Little Red Riding Hood became Cinderella, Cinderella became Snow White and who knows what else. But she was the greatest, she’d make your imagination come alive. It was such a fun time. I never wanted the story to end, and she’d go on telling them until I fell asleep. But my grandma on my dad’s side would be all the wolf ate her, the end! No, lady, it’s not over, I’d tell her, you don’t know the first thing about cartoon logic. She didn’t know that fairy tales aren’t supposed to end with someone dying. There had to be a happy ending.”

“It sounds like the poor woman never read Propp.”

“Probably not, she can’t read,” she said, adjusting the brim of her red baseball cap.

“You hit your grandma for no reason. She was telling you an early version of the story based on an even earlier version that’s more than a thousand years old.”

“How does that one end?”

“The wolf goes to bed with Little Red Riding Hood. That’s the end of the story.”

“Huh. He goes to bed with her? So they…?

“Uh-huh.”

“But that’s not a kid’s story.”

“Yeah, before Little Red Riding Hood was a fairy tale for kids, it was a fairy tale told in French villages. People would entertain themselves with a story of rape, or simply an erotic story, since most people say Little Red Riding Hood lets herself be seduced, and sleeping with the wolf takes her from adolescence into adulthood.”

“Wow, she must’ve been a real whore!” she said, laughing and evoking his laughter.

They were in Tokbashqe park, where he went most mornings to walk and to get some fresh air into his weak lungs. The park had greenery, flowers, color, and sun, naturally.

“So, at the very beginning, the bad guy wasn’t a wolf, but a man-wolf, a lycanthrope, or a werewolf. In the middle ages, when they had those awful trials, people who were suspected of being werewolves were persecuted, tortured and killed in the most horrific ways.”

“What did the werewolves do?”

“They’d howl,” he said, throwing his head back. He liked the term better than the more subtle yowl.

“Vampires?”

“Then they would eat Little Red Riding Hoods,” he added narrowing his eyes on her red hat.

“So they actually ate young girls?”

“That’s what they used to say. Society was superstitious. Maybe girls were being raped and werewolves were the ones being blamed for it. Or maybe they also raped girls, but they definitely didn’t eat them. The most they could do was sleep with the girls, and then they had the material for stories they’d tell in the taverns. They’d get drunk and start spinning fantasies between burps and belches.”

“So the wolf was a person?”

“Looks like it.”

“Or a person was a wolf?”

“You could say that, too.”

“Ugh, fairy tales!”

“No fairy tale is simply a fairy tale.”

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with being a wolf.”

“Guess not.”

“You live alone…”

“And when you do go out, you go out with wolves as opposed to dogs…”

“You eat fresh meat…”

“Howl at the moon at night…”

“Oh, yeah! That’s the coolest part…”

“…and the most meaningful.”

She looked into his eyes and lowered her head.

“Why are your eyes so red?”

“All the better to see you with,” he replied, unbothered that she had addressed him informally, and that this chance encounter was their first one alone.

She laughed. “No, no, seriously.”

“Because I wasn’t lucky enough to have blue ones.”

“Ah, only Little Red Riding Hood could have blue eyes,” she said, batting her eyelashes. She touched her hat with her right hand and he saw that her nails were painted blue.

Everything about her left an impression on Max—her Slavic facial features, the small nose, full lips, breasts that appeared large under her zip-up. In short, he liked everything about her—but her blue eyes, above all, astounded, struck, and stirred something in him. They were the eyes of Elsa of Aragon. Your eyes rival the bluest skies, he recalled.

“Do you think the director was right to pick me for the role of Judith?” she asked.

“If I’d known that someone like you would get the role, I would’ve written it a lot better.”

“The script is so long, it’s killing me. If you’d made it shorter it would’ve been easier to learn.”

“The director can shorten it.”

“You know the director? He said he can’t because then the audience wouldn’t be able to stand you. Seriously, he says you’re insufferable, and that you’re…full of yourself.”

“Full of myself? Well, great works never came from small minds.”

An older couple walked past them, the woman’s spine bent into a concave curve whereas the man’s bent into a convex one; she sniffed the ground, he, the sky.

“And what do you think of Judith?” Max asked Little Red Riding Hood.

“I’ve read worse,” she replied, making a fist and gripping the brim of her hat with just her middle finger. He understood the hand gesture. However much he tried to be serious, one corner of his mouth betrayed him.

“Are you married?” she said, suddenly changing the subject.

He shot her a look as if to say “well, now you’ve gone too far. Even freedom has its limits.” But he didn’t say it, only observed her quietly.

“You don’t remember?” she asked sarcastically, licking her lips.

He smiled. The smile was a sign of submission to her sexual innuendos that, it seemed, he didn’t plan to call her out on.

“No, I’m not,” he replied, finally.

“So, you live alone, I assume?” she pressed again.

“No.”

“With who, then?”

“With my ghosts,” he said and looked away at the people running around the track in shorts.

“Got a cigarette?”

“No, Little Red Riding Hood. And I don’t think you should smoke. You don’t come to the park to smoke.”

“Thanks for your concern, papa wolf,” she said, placing the stress on the last two words both to remind him of his age and to turn him on.

He was looking at her, but she had lowered her head and was searching her pockets for a cigarette and a match. She lit the cigarette. His gaze moved from the brim of her red cap to her round, red lips. She placed her white cigarette softly between them. Oh, how I’d enjoy eating you, the wolf thought to himself, and said aloud, “I have to go.”

She looked at him with surprise. Either she didn’t understand what had come over him or pretended not to.

“It was good to meet you,” he said, and left.

“Hey, pops, before you go, could you recommend a song?” she said, gesturing toward her headphones.

It didn’t take him long to come up with “Li’l Red Riding Hood by Sam the Sham & the Pharaohs.” And with that, he left, feeling out of breath.

She looked the song up on her phone and, before putting her earbuds back in and going to the bench where her friends, dressed in sport attire, stood waiting for her, she said:

“Are you here every day?”

“Not every day… but often.”

“You clearly need it, your belly’s getting pretty big. Looks like you ate Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother.”

He only smiled, without turning his head to notice that she was flicking him off as she danced to the song:

Owo!

Who’s that I see walkin’ in these woods?

Why, it’s Li’l Red Riding Hood.

Hey there Li’l Red Riding Hood,

You sure are looking good.

You're everything a big bad wolf could want.