The storyline unfolds around a missing person since the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus. Nikiforos, a 19-year-old soldier of the national guard, doing his military service in the 361st infantry battalion on Pentadaktylos mountain range is missing in action. Nikiforos himself, as every other missing person, knows exactly what happened to him, and led to his “disappearance” and death. Those who are ignorant and live through this vanished person situation are people close to him; survivors like his siblings Hermes and Julia, Aunt Fani, Savvas his friend. Even Michael, Julia’s son who was born 28 years after Nikiforos went missing, thinks about him, makes assumptions, has feelings and fears associated with his uncle’s circumstances(fate). The background being the present time, which the characters observe, ponder and discuss, whilst getting on with their everyday life, we follow Hermes, Julia, Michael, Savvas and Michael. By studying their thoughts and feelings, the hidden connections that connect them with Nikiforos unravel. As a few bone fragments of his are identified and matched as “him”, things darken and climax. The story ends with a scene which is completely different in ambience from the main body of the Outpost - a magical catharsis.

Agent / Rights Director

Publishing House

Excerpt

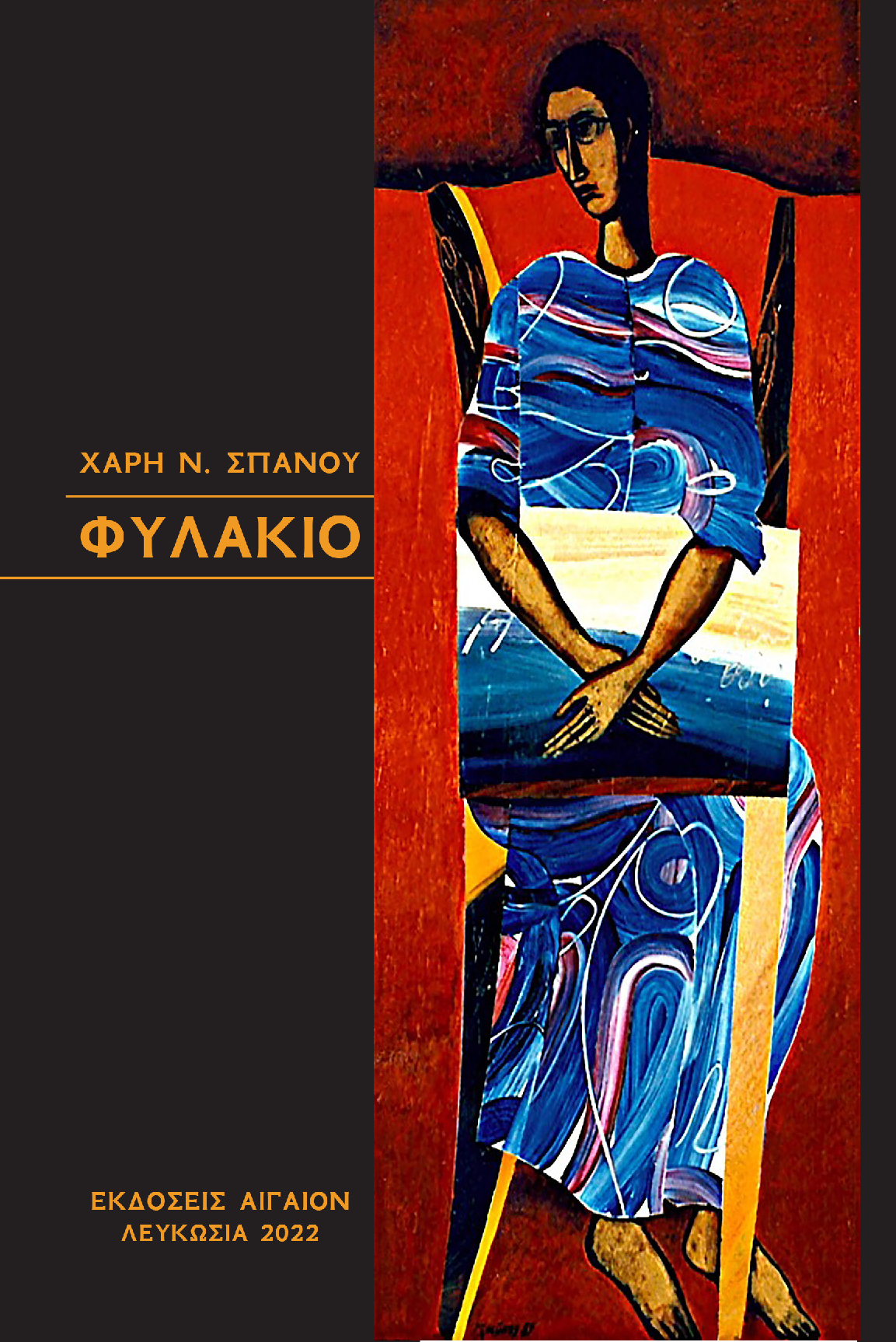

Φυλάκιο

Χάρη Ν. Σπανού

Εκδόσεις Αιγαίον, 2021

ΙΟΥΛΙΑ

Δασύτονο άγος

Θυμός – ένας αρχέγονος τρόπος να ενδύει κανείς τη Θλίψη του.

Θλίψη, Απώλεια, Θυμός. Ζωή, Φθορά, Αγωνία.

Θεμελιώδεις τριάδες.

Το μεσημέρι λοξοδρομώ από τον αυτοκινητόδρομο προς τα ημιορεινά. Σταθμεύω και βγαίνω από το αυτοκίνητο. Βα δίζω για καμιά ώρα με ταχύ βήμα, θαρρείς θέλω να τρυπή σω τη Γη με τις πατούσες μου. Ύστερα πάλι οδηγώ. Ο νους μου τρέχει. Η θάλασσα ίσως να μπορεί να ξεπλύνει για λίγο την Αγωνία. Ιστορίες για αγρίους.

Δυαδικός βηματισμός. Με τον άντρα μου περπατούσαμε τέσσερις πέντε φορές την εβδομάδα. Ο διασκελισμός μας ταίριαζε, ήταν συγχρονισμένος. Κουβεντιάζαμε πολύ∙ πολλές φορές συμπλήρωνε ο ένας την πρόταση του άλλου – όχι οποιαδήποτε πρόταση για τα καθημερινά, άλλωστε δεν πολυμιλούσαμε για τα καθημερινά. Ξέρω πως δεν είναι συχνό το φαινόμενο στα ζευγάρια∙ αυτό δεν σημαίνει ότι δεν διαφωνούσαμε, αλλά ότι βρισκόμασταν «on the same page». Σπάνιο κι αυτό. Το μάτι του Ερμή τα πιάνει αυτά, μας πείραζε όταν μας έβλεπε να χορεύουμε – ε ναι, χορεύαμε, χαιρόμα σταν. Η νιότη μας συνέπεσε με χρόνια δύσκολα∙ όταν περνά δύσκολα ο άνθρωπος, τότε μαθαίνει να γιορτάζει τη ζωή. Υπονοώ πως τώρα, που όλα μοιάζουν κανονικά, δυσκολεύ εται ο κόσμος να γιορτάσει με την ψυχή του∙ θέλει βοηθήματα: χαπάκια, σφηνάκια, ποτάκια. Όλα υποκοριστικά, όπως έγραψε ο Σάββας Παύλου.[1] Εξωφρενικά δυνατή μουσική, σαν να εμποδίζει το είναι σου να ψιθυρίσει. Δεν είναι ρετρό τα γούστα μου, αλλά η τωρινή διασκέδαση θυμίζει γήπεδο: φώτα, φωνές, χοροπηδητά, χειρονομίες, συνθήματα. Μια αγωνία ατέρμονη.

Δύσκολα χρόνια σημαίνει σκιά θανάτου να παραμονεύει

– η αντίθεση με τη νιότη, τη χαρά, τον έρωτα, τη φιληδονία ήταν χτυπητή. Δεν ήταν ασυνήθιστο να καταλήγουν τα γλέντια μας με σβησμένα μικρόφωνα, χαμηλόφωνη ψαλμωδία, δάκρυα και σούπα στα ξενυχτάδικα της πόλης. Λες και η σούπα παρέα με τους επαγγελματίες ξενύχτηδες ταξιτζήδες, πόρνες, χαρτοπαίκτες μας επανέφερε στην πραγματικότητα. Τώρα όλοι παριστάνουν ότι παίζουν σε αμερικάνικη σειρά – πέφτουν ξεροί / σηκώνονται / μπαίνουν κάτω από το δυνατό ντους / φορούν κολλαριστά πουκάμισα από ντουλάπες με δεκάδες άλλα και κινούν να κατακτήσουν τη ζωή της νέας μέρας.

Η ζωή είναι προς κατάκτησιν;

Κι εγώ που νόμιζα πως είναι για να τη ζεις.

Θυμούμαι τι έκανα όταν μπήκαν οι Αμερικανοί στο Κουβέ ιτ (ήταν η πρώτη φορά που τα βλέπαμε ζωντανά στην τηλεόραση), όταν τους χτύπησαν τους δίδυμους πύργους στη Νέα Υόρκη και όταν οι Αμερικανοί εισέβαλαν στο Ιράκ. Το ίδιο θα θυμούμαι, όσο ζω, πως σήμερα με ειδοποίησε η Διερευνητική Επιτροπή Αγνοουμένων για τον αδερφό μου τον Νικηφόρο∙ προέκυψαν κάποια «δεδομένα» και καλούν εμένα και τον Ερμή να πάμε στα γραφεία τους και μετά στο εργαστήριο. Το εργαστήριο ζωντανού θανάτου 1974 – έτσι έπρεπε να το λεν. Αφού αυτό είναι.

Και σαν τι «δεδομένα», άραγε, να βρήκαν για τον Νικηφό ρο; Τι να φανερώθηκε; Σαράντα εφτά χρόνια στη φαντασία μου ο τρόμος, το κακό, τα τέρατα όλου του κόσμου θαρρώ πως τρύπωσαν στο μυαλό μου και δεν άφησαν περιθώρια για τίποτε. Σαν τι «δεδομένα» θέλουν να μας μεταφέρουν; Βρήκαν τον αδερφό μου ολόκληρο, θαμμένο; Έναν φαντάρο που ατύχησε, σκοτώθηκε στον πόλεμο; Ή θα αρχίσουν τα ίδια με τόσων άλλων; Κομμάτια κοκκαλάκια σκορπισμένα σε ομαδικούς τάφους, σε πηγάδια, σε χωράφια χέρσα, πεταμένα σε λάκκους κρανία με τρύπες από χαριστικές βολές. Πόσα κακά, τι βάσανα κάναν στο αδερφάκι μου; Καταφτάνει η επιστήμη, καθαρή, φρεσκοπλυμένη από χώμα και αίμα, σε εργαστήρια με λευκά φώτα και μεταλλικούς πάγκους με φωτογραφίες, τοπογραφικά, σχεδιαγράμματα, DNA και ταυτοποιήσεις για να ταξινομήσει το κακό. Να κλείσει έναν φάκελο ακόμα. Να δώσει μια κούτα με «ευρήματα». Να τη θάψουμε με τιμές και σημαίες, να γραφτεί –πώς το λένε οι εφημερίδες;– «ο επίλογος της τραγωδίας». Εδώ σε θέλω κάβουρα.

Να αντέξεις τον επίλογο.

Όταν έφτασε στο σπίτι, είχε ξεθυμάνει. Μπήκε στο λουτρό. Έλεγξε τη θερμοκρασία του νερού και στάθηκε κάτω από το ντους. Άφησε το νερό να τρέξει πάνω της μέχρι που θάμπωσε για τα καλά ο καθρέφτης και το τζάμι. Δεν ήλπιζε πως θα ξεθώριαζαν οι εικόνες που πλημμύριζαν το μυαλό της, αλλά δεν μπορούσε να αντισταθεί στη ζεστή αγκαλιά του νερού. Η λευκή σαπουνάδα σχημάτιζε φυσαλίδες που ιρίδιζαν στο φως. Ή ήταν δάκρυα που τη θάμπωναν;

Ποιος ξέρει;

Φρεσκολουσμένη με τις πιτζάμες, έχωσε το κεφάλι της από τη μισάνοιχτη πόρτα του υπνοδωματίου. Ο Μιχαήλ καθόταν στο πάτωμα και τακτοποιούσε τα ηλεκτρονικά παιχνίδια στο χαμηλό ράφι της βιβλιοθήκης.

«Καλησπέρα, δεν θα βγεις απόψε;»

«Μπα, μπορεί να φάω σπίτι. Τι θα παραγγείλουμε;» Η Ιουλία δοκίμασε να τον δελεάσει.

«Έστειλε η νονά σου φρέσκο κοτόπουλο – έφτιαξα σούπα αυγολέμονη. Να τηγανίσω τα συκωτάκια, τα θέλεις; Έφερα φρέσκο ψωμί».

Την κοίταξε κοροϊδευτικά.

«Νέο κόλπο; Από πότε τηγανίζεις; Ίσα ίσα επιμένεις, σχάρα-ατμός-κατσαρόλα».

Η Ιουλία γέλασε.

«Λυπήθηκα να τα πετάξω. Η όρνιθα είναι από την αυλή της, άρα τα συκωτάκια νόστιμα. Ή εσύ θα τα φας ή ο Μαξ θα απολαύσει αυτοκρατορικό φαΐ».

Ο Μιχαήλ σηκώθηκε.

«Αν πεις όρνιθα ξανά, δεν θα φάω! Κοτόπουλο, μάνα. Ο Μαξ θα φάει στήθος».

Το κόκερ μπήκε τρέχοντας στο δωμάτιο –άκουσε το όνομά του δυο φορές– και πήδηξε χαρούμενο στα πόδια του Μιχαήλ. Εκείνος πέρασε την παλάμη του από το κανελί του κεφάλι και χάιδεψε τα αυτιά του.

«Άντε, Μαξ, θα φάμε αμαρτωλά απόψε!»

Τα μάτια του Μαξ σπινθήρισαν ενώ τραβούσε τον Μιχαήλ από το μανίκι.

«Θα πάμε για μια γρήγορη βόλτα εμείς και σε μισή ώρα θα είμαστε στο τραπέζι. Μαξ, θα φάμε “όρνιθα”, ακούς κι εσύ». Το κόκερ ήδη βρισκόταν στην εξώπορτα με το λουρί στα δόντια και χοροπηδούσε επί τόπου χωρίς να μπορεί να κρύψει τον ενθουσιασμό του.

Η υπόθεση κεραμική γεννήθηκε τα τελευταία είκοσι χρόνια της ζωής μου. Ωσάν να γέννησε ο γάμος μας τρία παιδιά και τον πηλό. Χρειάστηκαν χρόνια για να ωριμάσει.

Θυμούμαι γύρω στο 2000 όταν περιδιαβαίναμε με τον Σάββα τα ορεινά χωριά της Πιτσιλιάς που ξαφνικά θύμωσε, έγινε φονιάς μπροστά σε μια εκκλησία με κάμποσα πιθάρια στημένα στη σειρά σαν σε εκτελεστικό απόσπασμα. Όταν ξεθύμανε κάπως, μου εξήγησε ότι θεωρούσε ασυγχώρητη ανοησία το γεγονός ότι γόνοι χωρικών, των οποίων όλο το βιος και η ζήση βασίζονταν στα κρασοπίθαρα, τα κουμνιά, τα πιθάρια του λαδιού, τα κόσκινα, τα εργαλεία κάθε λογής, τους αργαλειούς, είχαν την αναίδεια να τα μετατρέπουν σε φολκλόρ, παριστάνοντας τους αρτιστίκ. Άρχισα τότε να παρατηρώ συστηματικά αυτή τη συνήθεια της εποχής. Οι περισσότεροι γεμίζουν τα πιθάρια με λουλούδια ή φοίνικες

– τα στήνουν σε κήπους, στα σπίτια, στα ξενοδοχεία. Αυτό συνέβη εδώ και πενήντα χρόνια – τώρα πια είναι λες και εθίστηκαν όλοι να μετατρέπουν στοιχειώδη χρηστικά αντικείμενα σε ντεκόρ. Βοήθησε και ο τουρισμός. Τα πράγματα γρήγορα χειροτέρεψαν. Δεν έμεινε τίποτε∙ σαν οδοστρωτήρας η νέα εποχή εξολόθρευσε έναν κόσμο αιώνων. Κι ύστερα, σαν σε χοντρό αστείο, εμφανίστηκε η απάτη των περιβαλλοντιστών. Παγιδευμένοι κι αυτοί στην ίδια τρέλα της ανάπτυξης. Τη βάφτισαν, μάλιστα, πράσινη και αειφόρο. Τι βαριά λέξη∙

«αειφόρος», όπως το «αθάνατος». Τι ξέρουν οι άνθρωποι για αειφορία; Εφόσον κατεξοχήν ασχολούνται με τη θνητότητα. Όταν πέθανε ο Σάββας, κοιμόμουν πλάι του. Με ξύπνησε ένας ήχος, δεν ήταν βρόγχος ή κραυγή∙ ήταν ένας ήχος βαθύς σαν να έβγαινε από τα έγκατα της γης. Πρόλαβα να δω τα μάτια του πριν δραπετεύσει η ζωή. Δεν είχαν ούτε φόβο ούτε απελπισία ή γαλήνη ούτε κάτι που μπορώ να το πω με λόγια. Αδυνάτισαν οι λέξεις ή εγώ αδυνατούσα να βρω λέξη να αντιστοιχεί με την τελευταία του ανάσα ή το βλέμμα του. Πήρα έναν μήνα άδεια μετά τον θάνατό του. Ήταν μια περίοδος σαν λαβύρινθος∙ δεν έβρισκα άκρη, δεν μπορούσα να βάλω τίποτε σε τάξη. Η απώλεια δεν έμπαινε σε τάξη. Έπρεπε να βρω έναν άλλον τρόπο για να ζω. Με τον Σάββα ήμασταν μαζί από τα νιάτα μας∙ από φοιτητές. Διέφερε από τα αδέρφια μου – ήταν φίλοι αχώριστοι με τον Ερμή και τον Νικηφόρο, αλλά ήταν αλλιώτικος. Ζούσε και σκεφτόταν με τρόπο θαρρείς… ζωικό. Τα θεωρητικά σχήματα τον άφηναν αδιάφορο. Δεν ήταν διανοούμενος, πώς να το εξηγήσω; Ήταν άνθρωπος της ζωής∙ έμοιαζε περισσότερο με μέλισσα. Θυμούμαι κάποτε μια συνέλευση που τράβηξε ώρες ατελείωτες στο πανεπιστήμιο. Έντονη συζήτηση, κόντρες, απόψεις, τι να κάνουμε, πώς να το κάνουμε, έτσι, αλλιώς και αν και μήπως. Φεύγοντας τα χαράματα, ο Σάββας άφησε ένα τετράδιο ιχνογραφίας στο προεδρείο. Είχε καμιά δεκαριά σκίτσα για αφίσες διαμαρτυρίας – ήταν το 1983 όταν ανακηρύχθηκε στα κατεχόμενα το ψευδοκράτος. Ήταν περίεργο το κλίμα τότε∙ δεν είχαν περάσει ούτε δέκα χρόνια από την εισβολή. Δεν ξέραμε, θα χτυπήσουν; Θα αντιδράσουν οι δικοί μας; Ο Σάββας άφησε το τετράδιο στο τραπέζι και μου είπε: «Αυτά είναι προτάσεις για αφίσες. Οτιδήποτε άλλο, θα φανεί∙ αν χρειαστεί, θα κατέβουμε κάτω να αμυνθούμε. Ό,τι περνά από το χέρι μας. Τα άλλα είναι κουβέντες δίχως νόημα».

Του πήγαινε που ήταν μηχανικός. Έκανε διδακτορικό στην αντοχή υλικών, ενώ ταυτοχρόνως δούλευε στη βιομηχανία. Όταν γεννήθηκαν τα παιδιά, συνεχώς κατασκεύαζε διάφορα, απλά και σύνθετα – ξύλινη κρεμάστρα για τα μόμπιλε να παίζει το βρέφος ενώ ξαπλώνει στο κρεβάτι ή το κάθισμά του, ένα σκηνικό κουκλοθεάτρου με στηρίγματα ώστε να είναι στη σκηνή πολλές κούκλες, όχι μόνο δύο, όσα και τα χέρια του παιδιού. Παθιάστηκε να φτιάξει ένα δεντρόσπιτο στη βαλανιδιά της αυλής χωρίς να το πάρουν είδηση τα μικρά. Τους είπε ότι το δέντρο ήταν άρρωστο και το σκέπασε με κάτι πράσινους μουσαμάδες ώστε να μην πλησιάζουν και μέσα σε δέκα μέρες το έφτιαξε. Είχε σκάλες μπροστά και πίσω, βεραντούλα, παραθυράκια, πέρασε και καλώδια και τους έβαλε ρεύμα. Έμεναν ώρες και έπαιζαν. Να φανταστείς πήραν και μικρή σκούπα και φτυαράκι και καθάριζαν. Δεν καθόταν ήσυχος. Αν δεν σκάλιζε ή έχτιζε κάτι, σχεδίαζε κάτι άλλο: βιβλιοθήκες, τραπεζάκια, πάγκους. Όταν τον βαρι όμουν με την ανακατωσούρα που προκαλούσε, πήγαινε στο χωριό, στο σπίτι της πεθεράς μου που είχε μπόλικο χώρο και έβρισκε απασχόληση.

Στη γειτονιά μας ζούσε ο Σταμάτης που είχε κεραμείο. Όταν πέθανε ο Σάββας, πήγαινα στον Σταμάτη και καθόμουν. Ήταν λιγομίλητος άνθρωπος, γι’ αυτό και δεν περίμενε να μιλήσω. Σιγά σιγά μαγεύτηκα από τον πηλό. Το ζύμωμα, το πλάσιμο, τα καλούπια. Αυτό ήταν. Δεν έχανα ευκαιρία, πεταγόμουν στο κεραμείο. Έκανα μαθήματα, μετά έψαξα να βρω τα ντόπια χώματα, γιατί, ενώ είναι πανάρχαια η τέχνη του πηλού στα μέρη μας, οι περισσότεροι δουλεύουν εισαγόμενο πηλό. Μου πήρε τρία χρόνια να αποφασίσω να φύγω από τη δουλειά. Ήταν καλή απόφαση. Τώρα πλέον, εκτός από τέχνη, είναι και βιοπορισμός. Είναι η ζήση μου.

Και η ζωή μου που σημαδεύτηκε από τον θάνατο. Όπως όλων των θνητών.

Μέχρι να στρώσει τραπέζι άκουσε το γάβγισμα του Μαξ στην εξώπορτα. Ο Μιχαήλ μπήκε στην κουζίνα.

«Ωραία μυρίζει. Είναι έτοιμο, να κάτσω;» Η Ιουλία έγνεψε:

«Κοπιάστε!»

Κάθισαν αντικρυστά στο στρογγυλό τραπέζι. Ο Μιχαήλ εφόρμησε με όρεξη στο φαγητό. Η Ιουλία γέμισε το ποτηράκι της ζιβανία.

«Θα πιεις;»

Ο Μιχαήλ, σκυμμένος πάνω από το πιάτο, ύψωσε τα φρύδια του.

«Το ρίξαμε στα σκληρά, μάνα; Βάλε μου λίγη».

Για λίγη ώρα ακουγόταν μόνο η κλαγγή των μαχαιροπίρουνων. Ο Μαξ μπήκε στην κουζίνα και έτριψε τη μουσούδα του στα πόδια της Ιουλίας. Εκείνη ξεσκέπασε την κούπα και την έβαλε στη γωνιά, δίπλα στο νερό του. Το σκυλί, κουνώντας την ουρά του, άρχισε να τρώει.

Η Ιουλία επέστρεψε στο τραπέζι.

«Μου τηλεφώνησαν από τη ΔΕA[2] σήμερα», είπε ουδέτερα. Ο Μιχαήλ ανακάθισε και, ακουμπώντας το πιρούνι στο πιάτο, έβγαλε από την τσέπη τον καπνό, τα χαρτάκια και τα

φίλτρα του.

«Τι σημαίνει αυτό;»

«Σημαίνει ότι προέκυψαν στοιχεία για τον Νικηφόρο. Θα πάμε με τον Ερμή την Πέμπτη. Θα φανεί, δεν λένε τίποτε από το τηλέφωνο. Είναι ανάγκη να καπνίσεις;» διαμαρτυρήθηκε ξέπνοα.

«Θα βγω έξω. Άμα θες, έρχομαι μαζί σου», είπε χαμηλόφωνα. «Η σούπα είναι επί τη ευκαιρία; Για παρηγοριά;» Πέρασε το χέρι από τα μαλλιά του. «Τώρα βλακείες λέω. Είσαι καλά;»

Η Ιουλία χαμογέλασε.

«Καλά είμαι». Δίστασε και πρόσθεσε: «Καλά θα είμαι. Μου ήρθε σαν αστροπελέκι∙ έτσι θα ερχόταν, αλλά… προετοιμασμένη δεν ήμουν. Μετά την τελευταία φορά που ξέρεις, είχαμε νομίσει όλοι πως θα τον έβρισκαν και δεν…»

Έκανε μια παύση και σιώπησε. Ο Μιχαήλ πήγε προς τη βεράντα, η Ιουλία τον ακολούθησε. Όρθιος, ακουμπώντας στον τοίχο, άναψε τσιγάρο ο Μιχαήλ, φύσηξε τον καπνό που έπνι ξε έναν βρυχηθμό κι έβηξε. Η Ιουλία έσκυψε στα φυτά και μάζεψε μερικά ξερά φύλλα από τις γλάστρες.

«Να χαρείς, μάνα, μην τρελαθείς όπως την άλλη φορά. Κάτσε να δούμε τι θα πουν».

Η Ιουλία πέταξε τα ξερά στον κάδο και τον έκλεισε. Γύρισε τον μοχλό και ακούστηκε ο υπόκωφος ήχος της ανάμειξης. Τίναξε τις παλάμες της.

«Δεν είχα τρελαθεί ακριβώς. Έτσι το θυμάσαι;» Ο Μιχαήλ μετάνιωσε.

«Κάπως πρέπει να το πω. Κι οι δυο, κι εσύ κι ο πατέρας, ήσασταν κάπως εκτός. Ο Ερμής και η Φανή ήταν ψύχραιμοι. Παλιά ξινά σταφύλια – έτσι δεν το λες;»

Η μάνα του γύρισε την πλάτη.

«Έτσι είναι η έκφραση, εγώ πάω μέσα, κάνει ψύχρα».

Μπήκε στην κουζίνα να τακτοποιήσει. Καθώς έπλενε τη χύτρα, ο Μιχαήλ έσκυψε και τη φίλησε στο μάγουλο.

«Καλά, θα δούμε. Εγώ θα πεταχτώ στης Ουρανίας».

«Καληνύχτα, μην ξημερωθείς».

[1] Σάββας Παύλου, Φώναξε τα παιδιά, σελ. 27, «Τα επικίνδυνα υποκοριστικά», εκδόσεις Κουκκίδα, Αθήνα 2015.

[2] Διερευνητική Επιτροπή Αγνοουμένων.

Excerpt - Translation

The Outpost

Hari N. Spanou

Translated into English by Patricia Barbeito

Julia

Οf honor and awe

Anger – a tried and true method of veiling one’s Grief.

Grief, Loss, Anger

Life, Decay, Anguish

Essential triads

In the middle of the day, I veer off the highway towards the foothills. I park and get out of the car. I walk for about an hour at a rapid stroll, as if trying to pierce the Earth with the soles of my feet. Afterwards, I drive some more. My mind is going a mile a minute. Perhaps the sea may succeed in washing away the anguish for a while. Quirky stories.

A double tread. My husband and I used to take walks four, five times a week. Our stride was well paired, synchronized. We talked a lot; often we used to finish each other’s sentences – not just any old sentence about our daily routines; besides, we didn’t often talk about routine. I know it’s not a common phenomenon for couples. This does not mean that we always agreed, but simply that we were “on the same page.” That, too, is rare. Hermes, who was always perceptive about such matters, would tease us whenever he watched us dancing – yes, that’s right, we would dance; we were happy. Our youth coincided with a difficult era, and when a person goes through tough times, they learn how to celebrate life. I’m alluding to the fact that now, when everything seems so normal, people find it hard to truly celebrate, wholeheartedly. They seem to need so much help: a few little pills, a few little shots, a little alcohol. A little bit of this, a little bit of that – so many diminutives, as Savvas Pavlou once wrote.[1] Then, there’s the outrageously loud music that seems to be trying to keep our very beings from muttering. It’s not that my tastes are retro, but the current entertainments remind me of an evening watching sports at the stadium: bright lights, noise, jumping up and down, broad gestures, slogans. An endless anguish.

Difficult years means the lurking shadow of death. The contrast with youth, joy, love, hedonism was striking. It was not unusual for our parties to end with switched off microphones, quiet chants, tears and soup in the town’s late-night joints. As if a bowl of soup in the company of the nocturnal professions – taxi-drivers, prostitutes, card players – would bring us back to reality. Now, everyone acts as if they are playing a part in an American television serial: they fall into bed like a sack of potatoes, get up, stand under a strong shower, throw on a starched shirt chosen from a wardrobe full of dozens of others just like it, and off they go to conquer yet another new day of life.

Is life something to be conquered?

Silly me, I thought it was something to be lived.

I still remember what I was doing when the Americans entered Kuwait (it was the first time that we watched something like that live on television); when New York’s Twin Towers were attacked; and when the Americans invaded Iraq. Just as I will always remember, for as long as I live, that today the Committee on Missing Persons contacted me to say that they have found some new “data” concerning my brother, Nikiforos, and to invite me and Hermes to their offices and then to the laboratory. The laboratory of the living dead 1974 – that’s what they ought to call it. Because that is what it is.

What kind of “data,” I wonder, have they found concerning Nikiforos? What has come to light? For forty-seven years, terror, evil, the monsters of the entire planet have lurked in my imagination. So much so that I feel as if they have burrowed into my brain and crowded out anything else. What kind of “facts” do they now want to relay to us? Have they found my brother buried in one piece? Just one of those unlucky soldiers killed in war? Or will they start the same song and dance that they have started with so many others? Tiny pieces of bone scattered in mass graves, in wells, in uncultivated fields; skulls shattered by merciful deathblows and tossed into holes in the ground? How much torture did my brother endure? What torments did he have to suffer? Freshly cleansed of all the dirt and blood, all purity and brightly-lit laboratories full of metal counters, photographs, contour maps, diagrams, DNA, and identifications, science charges in to taxonomize evil; to close yet another file; to hand over a box of its “findings”; to ensure that we bury them with all due pomp and flags waving, and that, as the newspapers put it, we get to the “epilogue to the tragedy.” And that my friends, is the million-dollar question.

How does one get through that epilogue?

By the time she got home, all the anger had dissipated. She went to the bathroom, checked the water temperature, and stood under the shower, letting the water run over her until the mirror and the window had completely steamed up. She had no hope that the images flooding her brain would fade, but she could not resist the water’s warm embrace. The white lather made bubbles that shimmered in the light. Or was it the tears that were blurring her sight?

Who knows?

Hair freshly washed and in her pyjamas, she poked her head through the half-opened door to the bedroom. Michail was sitting on the floor and arranging his electronic games on the lower shelf of the bookcase.

“Hey there. You’re not going out this evening?”

“Nope. I may eat in tonight. What shall we order?”

Julia tried to tempt him. “I’ve made chicken-soup with the fresh chicken your godmother sent us. I could also fry up the livers. Would you like some? I have some fresh bread.”

He glanced at her, a teasing look in his eyes. “New tricks? Since when do you fry things? In fact, you’ve always insisted that its either grill, steam, or stew.”

Julia laughed. “I feel bad throwing it out. The fowl is from her yard, so the liver is sure to be delicious. Either you eat it, or Max will get a meal fit for a king.”

Michail got up. “If you say fowl again, I’m not eating! It’s chicken, mum. Max will eat the breast.”

Having heard his name uttered twice, the cocker spaniel trotted into the room and cheerfully leapt onto Michail’s legs. The latter ran his hand over the dog’s cinnamon head and stroked its ears. “Ah, Max, we’re going to eat sinfully well tonight!”

Max’s eyes sparkled as he pulled Michail by the sleeve.

“Let’s go for a quick walk and in half an hour we’ll be at the table. Max, we’re eating ‘fowl,’ do you hear?”

The spaniel was already at the front door with the leash between his teeth, skipping in place, unable to hide his excitement.

It was only in the past twenty years that I gradually became involved with ceramics. As if our marriage gave issue to three children and a lot of clay that took years to mature.

I remember that around 2000, when Savvas and I were roaming the mountain villages of Pitsilia, he suddenly got angry, murderously so in fact, in front of a church with a number of amphorae standing in a row as if before a firing squad. When he calmed down a little, he explained that he found the younger generation’s artistic feints unforgivable. There they were, offspring of villagers whose entire lives and livelihoods depended on wine pitchers, urns, olive oil amphorae, sieves, all manner of hand tools and looms, and they had the brazenness to turn them into folklore. I then began to consistently notice this affectation of the period. Most people fill their urns with flowers or potted palms and place them around their gardens, homes, hotels. This has been happening for the past fifty years – now it is as if everyone has become addicted to converting rudimentary functional objects into décor. Tourism played a role too, of course, and things went from bad to worse very quickly. Nothing remained, like a bulldozer the new era trampled over the world that had prevailed for centuries. Then, like a bad joke, came the environmentalists and their deceptions. They, too, trapped in the same madness for growth and development, which they chose to christen green and sustainable. What a heavy word, “sustainable,” very like “immortal.” What do people know of sustainability, when their one eminent concern is mortality? When Savvas died, he was sleeping at my side. I was woken by a noise, which was neither a rattle nor a cry, but a deep sound as if emanating from the bowels of the earth. I was in time to see his eyes before the life left them. They were free of fear, despair, peace, of anything that I can put in words. Either words failed, or I failed to find words to account for his final breath and the look in his eyes. I took a month of leave after his death. That time was like a labyrinth; I could not make sense of things; I could not put anything in order. Loss cannot be put in order. I had to find another way to live. Savvas and I had been together since our youth, since university. He was not like my brothers – he and Hermes and Nikiforos were fast friends, but he was different. He lived and thought in a manner that one might describe as …bestial. Theoretical formulations left him cold. He was not an intellectual, how can I explain? He was a man fully immersed in life, more like a bee than anything else. I remember a student assembly at the university that went on interminably, for hours. Heated discussions, arguments, opinions, what to do, how to do it, like this, like that, and perhaps not so let’s start all over again. At dawn, when he finally departed, Savvas left a sketch-book at the student center. He had made approximately ten drawings for protest posters – it was 1983, when the pseudo-state unilaterally declared independence in our occupied territories. The atmosphere was tense back then. Not even ten years had elapsed since the invasion. We did not know if they would attack again, or how our side might react. Savvas placed the sketchbook on a table and said: “I’ve made some drawings for posters. Whatever else is needed will become clear as we go. If we have to, we’ll go defend ourselves, and do what we can. Everything else is just a lot of hot air.”

The engineering profession suited him. He completed a Ph.D. focused on the endurance limit of various materials while at the same time working in industry. When the children were born, he wouldn’t stop building things, some simple, some elaborate: a wooden hanger to transport a child’s favorite mobile from crib to car-seat; a puppet theatre stage with supports for many more puppets than the two on a child’s hands. He was obsessed with building a tree house on the oak tree in the yard without the children knowing. He told them that the tree was sick and covered it with green canvas so they wouldn’t go near, and within ten days he had built it. There were ladders both in front and back, a small deck, windows, and even wiring for electricity. They played there for hours. They even had a tiny broom and dustpan to keep the place clean. He could not sit still. If he wasn’t puttering around or building something, he was making plans for something else: book shelves, side tables, benches. When I’d get tired of the mess he always made, he would go to the village, to my mother-in-law’s house, which was quite large, and would find something to do there.

Stamatis, the owner of a pottery workshop, lived in our neighborhood. When Savvas died, I would go there to kill some time. He was a man of very few words, which is why he did not expect me to talk. Gradually, the clay bewitched me. The kneading, the throwing, the trimming. That was it. I would dash over to the pottery studio at every opportunity. I took classes, then I tried to find local clay, because, even though the art of clay is ancient as can be in our part of the world, most people work with imported clay. It took me three years to decide to leave my job. It was a good decision. Now, besides an art, it is also a way of making a living. It is my livelihood.

It is my life, kneaded as it was by death. Like those of all mortals.

By the time the table was set, Max was barking at the front door. Michail entered the kitchen.

“Smells good. Is it ready? Shall I sit?”

Ioulia beckoned: “Sit!”

They sat across from each other at the round table. Michail pounced hungrily on the food, while Ioulia filled a small glass with zivania. “Will you have some?”

Bowed over his plate, Michail’s brows shot up. “Going for the hard stuff, are we? Ok, Mum, pour me a little.”

For a while only the clang of cutlery could be heard. Max pattered into the kitchen and rubbed his snout against Julia’s legs. She took the lid off his bowl and put it down in the corner, next to his water dish. Wagging his tail, the dog started eating.

Julia returned to the table. “They called me from the Committee on Missing Persons today,” she said, keeping her tone neutral.

Michail sat up in his chair and placing the fork on his plate, he pulled the tobacco, rolling papers, and filters out of his pocket. “What does it mean?”

“It means that they have information about Nikiforos. Hermes and I will go there on Thursday. We’ll see, they don’t usually say much over the phone. Do you have to smoke?” she complained breathlessly.

“I’ll take it outside. If you want, I’ll go with you,” he said in a low voice. “So, all this about the soup is what? Incidental? A consolation?” He ran his hand through his hair. “Oh, I’m being silly now. Are you OK?”

Julia smiled. “I’m fine.” She hesitated before adding. “I will be fine. It came like a bolt out of the blue. That’s the way it was bound to come, wasn’t it? But … I wasn’t prepared. After that last time – you know what I’m talking about – when we all thought they would find him and they didn’t…”

She paused, then went silent. Michail got up and went to stand in front of the terrace, Julia following behind him. Leaning against the wall, Michail lit a cigarette, took a deep inhale of the smoke to stifle a cry, and started coughing. Julia bent over the plants and plucked a few dried leaves from the pots.

“Please, Mum, don’t go crazy like last time. Let’s wait and see what they say.”

Julia threw the dried debris in the compost bin, closed the lid, and turned the crank, releasing a hollow rumbling. She raised her hands. “I wouldn’t say that I went crazy. That’s just how you remember it.”

Michail repented. “I must find a way to say this. Both of you, you and dad, were beside yourselves. Hermes and Fani were cool and collected. Been there, done that– isn’t that what you like to say?”

His mother turned her back to him. “Yes, that’s the expression. I’m going inside. It’s cold.”

She went back to the kitchen to clean up. As she was washing out the pressure cooker, Michail bowed down and kissed her on the cheek. “Alright, we’ll see. I’m going over to Ourania’s.”

“Good night. Don’t stay up too late.”

[1] Savvas Pavlou, Call the kids. “Those dangerous diminutives.” Athens: Koukkida, 2015, p. 27.