Maud Simonnot is a French writer. Her biography of the publisher Robert McAlmon, La nuit pour adresse (Gallimard, 2017), has received the Valery-Larbaud prize and was a finalist for the prestigious Medicis essay prize. After L'Enfant céleste, Goncourt selection and finalist for the Goncourt des lycéens 2020, L'Heure des oiseaux is her second novel.

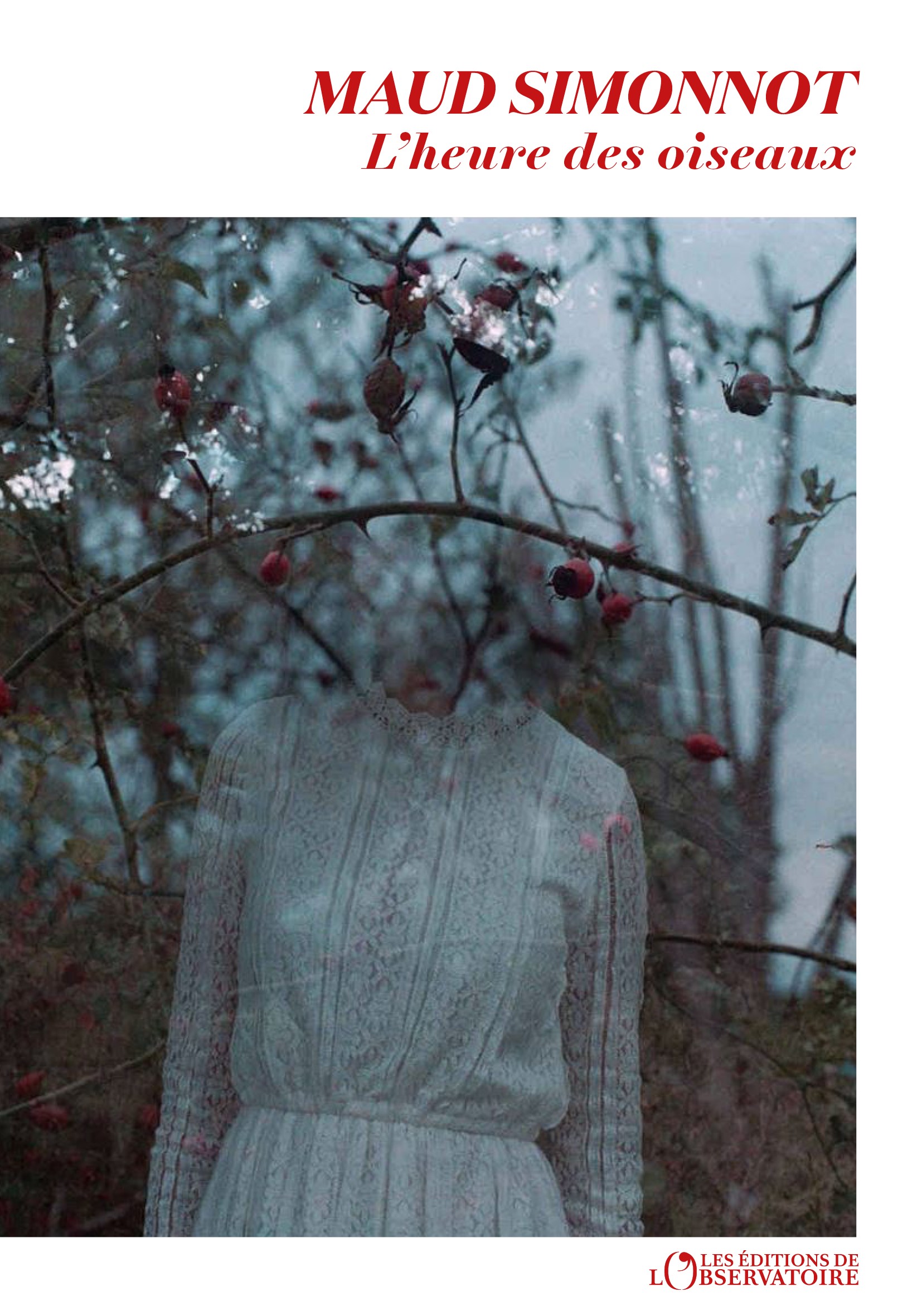

© Picture Olivier Dion

This novel is about the aftermath of the war on children and the abuse of innocent orphans, often the first victims of adult cruelty. The story takes place on Jersey Island in 1959. To avoid the cruelty and sadness of the orphanage, Lily, rejected as being different, draws all her courage from the song of the birds, her ability to re-enchant the world, the strange friendship she shares with a hermit in the “Forgotten Forest”, and the unconditional love she has for a young boy called “le Petit”. Sixty years later, a young woman, ornithologist travels from France to Jersey to investigate the past of her father, a pianist who also has a passion for birds. The islanders dodge the questions asked by this foreigner about the sordid affair linked to the orphanage… What happened to Lily and to his brother? What’s the drama kept secret for so long?

Agent / Rights Director

Publishing House

Excerpt

Maud Simonnot

L’heure des oiseaux

Éditions de l’Observatoire, 2022

Le jour où je suis arrivée sur l’île, il neigeait.

J’avais rêvé d’azur, de voiliers et de soleils couchants qui brûlent en silence, j’ai débarqué en pleine tempête dans un endroit où personne ne m’attendait.

Par facilité j’avais choisi un vieil hôtel dans un port du sud de l’île, près de la capitale, Saint-Hélier, à quelques kilomètres du lieu des crimes. Comme tous les villages bordant cette côte, celui-ci était bâti au creux d’une baie abritée des tempêtes. Mon guide précisait : « une superbe baie dessinée par des chaos de roches se perdant dans le bleu intense de la Manche ».

D’ordinaire le soir on pouvait voir, ajouta le patron de l’hôtel, le demi-cercle scintillant d’une guirlande qui ourlait la côte sur des kilomètres. J’étais prête à croire le guide et cet homme enthousiaste mais ce jour-là on ne distinguait pas son chien au bout de la laisse, et tout était d’un blanc triste, le ciel comme

la mer.

Dans mon esprit se superposaient aussi des images d’archives : j’avais vu un documentaire sur la Seconde Guerre mondiale dans les îles Anglo-Normandes et je savais qu’une attaque navale terrible avait illuminé autrement cette jolie anse, les fusées repeignant le ciel en vert et rouge, aux couleurs de l’enfer. Le grondement des canons avait retenti pendant des heures tandis que les sirènes du port hurlaient, recouvertes à leur tour par les cris, les bruits des bottes, les balles traçantes sur la plage…

*

Une fois dans ma chambre, j’ai laissé glisser le lourd sac de toile de mon épaule et passé l’appel téléphonique promis : « Oui, ça y est, je suis à Jersey. »

Lily voit que le Petit a encore pleuré. Parce qu’il a eu peur, parce qu’on lui a dit quelque chose d’effrayant, ou qu’on l’a grondé pour une faute inconnue. Sous la frange trop courte, mal coupée, de ses cheveux fins, les yeux clairs sont cernés.

Elle a une idée. C’est dimanche ; les adultes, après la messe, vaquent à leurs occupations à l’extérieur, l’orphelinat est vide. Elle court à la cuisine et revient avec quelques légumes dérobés

dans un panier du marché.

Il y aura la reine Rutabaga ceinte d’un chiffon blanc. Un œuf de caille trouvé au pied d’un mur, que Lily garde précieusement avec d’autres trésors sous son lit, sera parfait pour représenter l’enfant sur l’autel. Les reflets céladon de la coquille émerveillent le Petit qui n’en a jamais vu de semblables. Lily aligne les carottes comme des soldats de chaque côté et bâtit pour ses autres créatures un mobilier miniature à partir de branchettes.

Le spectacle commence. Le Petit oublie ses larmes, béat devant l’histoire qui se matérialise sous ses yeux. Lily a transformé l’atmosphère autour d’eux avec cette manière si particulière des enfants souverains, capable de réenchanter l’endroit le plus sordide et de créer un monde plus heureux.

Un instant.

Dès le lendemain, j’ai voulu voir l’orphelinat.

Face à moi s’élevait une immense bâtisse victorienne en granit, rendue plus lugubre encore par son histoire et le fait que depuis des années elle soit abandonnée aux vents et aux dégâts du temps. Un brouillard marin épais rejoignait un ciel cendré : le décor naturel était en harmonie.

Un des orphelins, parmi les témoins les plus importants du procès, avait déclaré qu’il souhaitait voir démolir cet endroit, symbole de son traumatisme. Dans ce sombre bâtiment bordant la forêt à la sortie du village, des dizaines d’enfants placés par l’Assistance publique avaient subi l’inavouable. Maltraitances physiques, humiliations, privations, punitions. Et, d’après plusieurs victimes qui avaient enfin parlé, sévices sexuels.

Tout avait débuté en 2008 lorsqu’on avait dégagé les restes d’un corps enterré dans une cave de l’orphelinat sous une dalle de béton. Un appel téléphonique anonyme avait précisé au commissariat l’emplacement des ossements. À partir de là, l’enquête était enclenchée : le chef de la police arriva sur les lieux et fit venir le médecin légiste, la route qui mène au pensionnat fut barrée – elle le resterait des années. Les premières constatations ne permirent pas de trouver le moindre indice supplémentaire, mis à part l’entrée dissimulée d’une autre cave, identique, dans laquelle des prélèvements furent effectués. Il s’avéra rapidement que les ossements provenaient d’animaux, c’était une fausse alerte. L’affaire aurait donc pu s’arrêter là mais, après la macabre découverte, les langues s’étaient déliées.

La presse locale évoqua des caves secrètes dans lesquelles des enfants auraient été attachés et enfermés sans rien à manger ni à boire, à l’isolement complet. Des journalistes de grandes rédactions anglo-saxonnes prirent le relais, tout s’emballa et le scandale médiatique entraîna une bien plus vaste investigation. Des lettres et des appels affluèrent de l’Europe entière. Au total cent soixante anciens pensionnaires racontèrent les violences infligées par des membres du personnel et certains visiteurs à partir de l’après-guerre. L’accumulation des témoignages et leur concordance ne permirent pas sur le moment de remettre en question leur parole.

Les policiers tentèrent de dresser la liste des personnes impliquées et celle des victimes. L’une comme l’autre furent difficiles à établir : l’orphelinat avait été fermé en 1986, on n’avait conservé aucun registre des employés ni des enfants. Dans l’enquête menée par la Jersey Child Abuse Investigation, une douzaine de spécialistes de la police scientifique furent chargés de la recherche et de l’identification de traces humaines qui pourraient raconter une histoire vieille de plus d’un demisiècle. Car d’autres témoignages signalaient aussi des disparitions d’enfants. La terre brune de l’île fut entièrement retournée aux alentours de l’orphelinat et les enquêteurs furent aidés par les plus fameux limiers du Royaume, deux épagneuls renifleurs déjà utilisés lors de la disparition de la petite Maddie. Mais on ne retrouva pas d’ossements, juste quelques objets tachés de sang, impossibles à identifier.

Et puis plus rien. Dans les médias, le doute sur ce qui s’était véritablement passé dans l’orphelinat s’était peu à peu installé, faute de preuves. La police locale, qui se divisait entre une police dite « officielle » et une police « honorifique » constituée de connétables, centeniers et vingteniers – des citoyens élus

depuis le xive siècle par les paroissiens pour « le maintien de l’ordre » –, était débordée par une si grosse affaire, rien n’avait pu être fait dans les règles. Des preuves avaient été égarées, les analyses et les témoignages se contredisaient, des informations censées rester confidentielles avaient circulé, certains témoins avaient été intimidés et étaient revenus sur leur déposition… Parmi les suspects encore vivants, trois seulement furent un temps inquiétés. On conclut à des « défaillances » dans la gestion de l’enquête, le chef de la police, dont l’intégrité gênait les notables locaux, servit de fusible et fut limogé. Last but not least, des experts en relations publiques furent engages pour redorer l’image du paradis fiscal. Dans l’île britannique, à vingt kilomètres des côtes françaises, l’onde de choc s’éteignit aussi vite qu’elle s’était levée et le bailliage de Jersey put recouvrer sa tranquillité légendaire, ses banques et son bocage verdoyant.

Le Petit a le front contre la vitre : « Il y a vraiment beaucoup de neige… » Son visage s’anime : « Imagine si c’était l’inverse, si le ciel était blanc et que les nuages et la neige étaient bleus ? »

En contemplant avec lui la course des nuages insouciants,

Lily est envahie de tendresse, elle aime tellement cet enfant rêveur :

« Tu aimerais sortir ?

— On a le droit ? »

Elle lui sourit, un doigt sur ses lèvres : « Suis-moi. »

Le garçon longe en trottinant le mur de la buanderie puis se glisse après elle derrière la réserve de bois jusqu’à une ouverture dissimulée dans le mur. Elle pousse la trappe, les voilà dehors dans la blancheur éblouissante de ce premier matin du monde.

Lily s’élance dans la neige vierge, si inhabituelle, qui a enseveli le parc. Tandis que le Petit expérimente cette étendue lisse et moelleuse, elle grimpe sur une souche pour s’approcher d’un nid en mousse encore accroché à une branche du vieux magnolia.

« Une famille de mésanges à longue queue vivait ici l’été dernier. Je les ai souvent vues. Les plus fragiles sont certainement mortes. »

Elle descend le nid précautionneusement, quelques cristaux de neige tombent de l’arbre. Les enfants défont les brindilles et comptent trois cadavres parmi les plumes floconneuses qui tapissent l’intérieur. Ensemble, ils creusent une tombe au fond du parc et recouvrent les oisillons de poudreuse et de feuilles

arrachées à l’herbe givrée. Le Petit hésite, et ose demander :

« Où sont le papa et la maman maintenant ? »

Lily ne sait pas.

Ce qu’elle redoutait arrive : le Petit enchaîne avec des questions sur leurs propres parents. Il faudrait qu’elle invente une histoire qui tienne la route, mais là encore aucune réponse ne lui vient.

Excerpt - Translation

The Hour of Birds

Maud Simonnot

Translated into English by Jeffrey Zuckerman

The day I come to the island, it is snowing.

I have dreamed of azure, of sailboats and setting suns blazing in silence; I debark in a raging storm someplace nobody has been expecting me.

For convenience’s sake, I chose an old inn on a harbor in the south of the island, by the capital, Saint-Hélier, a few miles from where the crimes happened. Like all the villages along this coast, this one has been erected inside a bay sheltered from storms. My guide clarifies: “a gorgeous bay formed by a mess of rocks amid the Channel’s intense blue.”

On most evenings, the innkeeper adds, people can see the gleaming half-circle of a wreath hemming in the coast for miles. I want to believe the guide and this enthusiastic man, but on this day I can’t make out the dog at the end of his leash, and sky and sea alike have a sad pallor.

Archival images, too, are overlaid in my mind: I once saw a documentary about World War II in the Channel Islands and I know a horrific naval attack lit up this pretty cove in its way, the rockets tingeing the sky green and red, in hellish colors. The cannons’ roar reverberated for hours while the harbor sirens shrieked, drowned out in turn by shrieks, thudding boots, tracers along the beach . . .

*

In my room at the inn, I slip the heavy canvas bag off my shoulder and make my promised phone call:

“Yes, I’m here, I’m in Jersey.”

Lily saw that The Boy was still crying. Because he was afraid, because he’d been told something scary, or scolded for some unknown mistake. Under the too-short, blunt-cut bangs of his fine hair, his light eyes had dark rings.

She had an idea. It was Sunday; after Mass, the grown-ups attended to matters outside and the orphanage was empty. She rushed to the kitchen and came back with a few stolen vegetables in a market basket.

There’d be Queen Rutabaga in a white rag. A quail egg found at the foot of a wall that Lily guarded jealously under her bed along with other treasures would be a perfect stand-in for the child on the altar. The shell’s celadon tones amazed the Boy who had never seen such hues. Lily lined up carrots like soldiers on each side and for her other creatures she built miniature furnishings out of twigs.

The performance began. The Boy forgot his tears, agape at the story unfolding before his eyes. Lily changed the atmosphere around them in this singular way only a haughty child could, infusing the most squalid places with newfound splendor and creating a happier world. In no time.

What I want the next day is to see the orphanage.

Before me stands a huge granite Victorian building, made even more stolid by its past and the fact that for years it has been left to the winds’ mercy and to time’s vicissitudes. A thick sea fog blurs into an ashen sky: the natural surroundings are in harmony.

One of the orphans, among the most important witnesses at the trial, said that he wanted to see this place, this symbol of his trauma, razed. In this dark edifice on the edge of the forest at the village’s entrance, dozens of children sent by Child Welfare endured unspeakable things. Physical abuse, humiliation, poverty, punishment. And, according to several victims who finally spoke out, sexual assault.

Everything began in 2008 when the remains of a body were unearthed beneath a slab of concrete in the orphanage’s cellar. An anonymous tip alerted the police to these bones’ location. And so the investigation began: the police chief arrived on the premises and brought in the forensic doctor, the road to the boarding school was blockaded—and would stay so for years to come. The preliminary findings turned up no further clues, apart from a hidden entrance to another, identical cellar. The remains taken from there soon proved to be merely animal bones: a false alarm. The case might have been closed there, after such a macabre discovery, but tongues were now loosened. The local papers described secret cellars in which children had been tied up and locked away without food or drink, in total isolation. Journalists from the bigger British papers stepped in, things snowballed, and the media furor set off a far more wide-ranging investigation. Letters and calls came in from all across Europe. All told, a hundred and sixty former boarders came to describe the violence inflicted upon them by the staff and some visitors beginning after the war. The sheer mass of eyewitness accounts and their consistency staved off any questions as to their factuality.

The police tried to draw up a list of people involved and another of victims. Both were difficult to authenticate: the orphanage had been shuttered in 1986, no register had been kept of employees or children.

The Jersey Child Abuse Investigation charged a dozen forensic specialists with finding and identifying any human traces that might shed light on a story over half a century old. Other accounts, after all, had indicated that children had died. Every inch of the island’s brown soil around the orphanage was turned over and the investigators were assisted by the United Kingdom’s best-known bloodhounds, two sniffer spaniels already used after little Maddie’s death. But no bones were found, just several bloodstained things that could not be identified.

And that was it. For lack of evidence, questions began to grow in the media about what had actually happened at the orphanage. The local police, which consisted of an “official” police and an “honorary” police made up of constables, centeniers, and vingteniers—citizens elected since the fourteenth century by parishioniers to “maintain law and order”—was out of its depth with such a sweeping affair, and little had been done in accordance with regulations. Evidence had been lost, analyses and accounts contradicted each other, confidential information had been leaked, some witnesses had been intimidated and had recanted their depositions . . . Among the suspects still alive, only three were worried. It was concluded that mistakes had been made in managing the investigation. The police chief, whose honesty was an embarrassment to the community leaders, was made a scapegoat and dismissed. To cap off matters, PR experts were hired to restore this fiscal paradise’s image. On the British island only twelve miles from the French coast, the shock waves subsided as quickly as they had come and the bailiwick of Jersey managed to regain its legendary tranquility, its banks, and its verdant landscape.

The Boy’s forehead was pressed to the window: “There’s lots and lots of snow . . .” His face lit up: “What if it was the other way around, what if the sky was white and the clouds and the snow were blue?”

As she contemplated the untroubled clouds with him, Lily was overcome with tenderness, she was fond of this daydreaming child: “Do you want to go outside?”

“Can we?”

She smiled, brought a finger to her lips: “Follow me.”

He scampered around along the laundry’s wall then followed her behind the wood stockpile to a hidden opening in the wall. She pushed open the trapdoor, and then they were outside, in the dazzling whiteness of this first morning in the world.

Lily launched herself into the untouched snow, a rare sight, that had buried the grounds. As The Boy experienced this smooth, soft expanse, she climbed onto a stump to reach a nest covered by a snowy foam still attached to a branch of the old magnolia tree.

“A family of long-tailed bushtits was here last summer. I saw them all the time. The weakest babies have to be dead.”

She brought down the nest carefully, a few snow crystals falling from the tree. The children pried apart the twigs and counted three corpses among the fluffy feathers papering the interior. Together, they dug a grave at the back of the park and covered the nestlings with powder snow and leaves pulled off the iced-over greenery. The Boy paused, and went so far as to ask: “Where are the ma and pa now?”

Lily doesn’t know.

What she feared had come: The Boy followed up with questions about their own parents. She needed to come up with a story that made sense, but in the moment no answers came.